Since America’s discovery, the various names given to our continent mirrored the conceptual ambiguity of the territory, and helped to prioritize the need for an identity. However, the analysis of the region as a cultural unity based on the permanent search for identity is a recipe that no longer works.

Non-definitions and stereotypes begin

« Latin American Art » is a term as elusive as the space that seems to give birth to it. How to talk about « Latin American Art » in times when geographic borders are more blurred and « deterritorialization » is a recurrent term in the context of theoretical studies in art and culture? As has been said by Santiago Castro-Gómez and Eduardo Mendieta: « (…) what is at stake is the very meaning of the expression ‘Latin America’ at a moment in History when cultural belongings of a traditional or national character seem to be replaced (….) by identities oriented towards transnational and post-traditional values »1 [my own translation from the Spanish].

This non-definition of the Latin American space, though with different connotations, is not unique of globalized times. In general, America has been historically evaluated and defined by the « Others »; repeatedly re-invented in accordance with the various imperialist projects of the great powers; or « created by opposition » to the nominal demarcation of its « Latin » part during the independence struggles of the nineteenth century. That permanent shifting of its conceptual outlines left frequent interstices, unknown or « in-between » spaces, which helped to blur its contours.

« The Indies » (later renamed as « West Indies ») was the first definition of our continent; a space where the European fantasy placed the most delicious and fantastic imagery, an uncontrolled mixture between the fear of the unknown and the classic and medieval teratology of the Old World.

This area remained « unknown » for a large period of time, unexplored by the colonial government, which devoted little efforts to study the new regions. In this regard, the exception was the botanical expedition led by José Celestino Mutis in the Vice-royalty of New Granada and those carried out in Brazil during the Dutch occupation (examples of which are the works of Franz Post and Albert Eckhout).

In contrast to the Spanish name of West Indies, in the non-Hispanic Europe the name of «America » emerged in honor of Americo Vespucci. This was also a symbolic way of challenging the exclusive power of the Iberian nation over the newly discovered territories2. With the arrival of the nineteenth century, the name of America took a particular importance, and ended naming at the same time a continent and a new nation (United States of Americas). This is the time when « Latin America » emerges as a counterpart of Anglo-America, and based in a supposedly common heritage, seeks to establish links with one of the emerging powers at the time: France.

1992, p. 88

First named by mistake (Indies), then necessarily re-named (West Indies), designated differently at the same time (America), and finally grouped by a supposedly common Latin heritage that eventually left out a large part of its inhabitants (indigenous population, people from the Francophone or Anglophone Caribbean, among others); not by chance, for many experts, the matter of identity is a substantive characteristic of our definition.

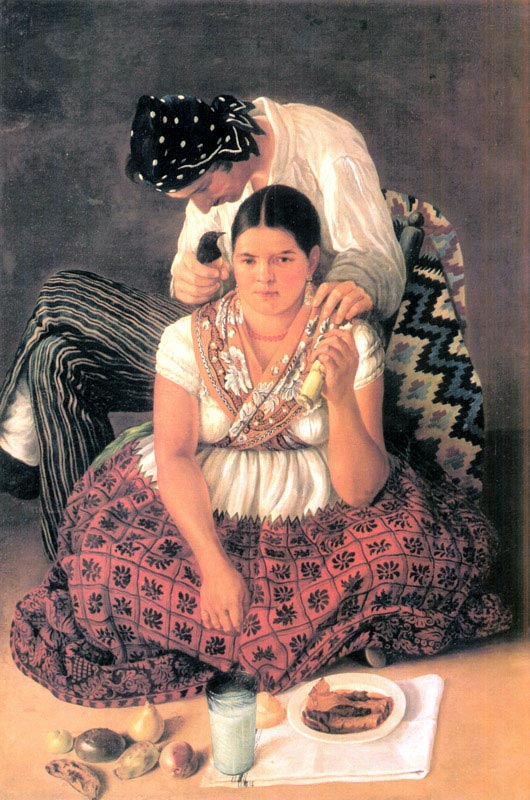

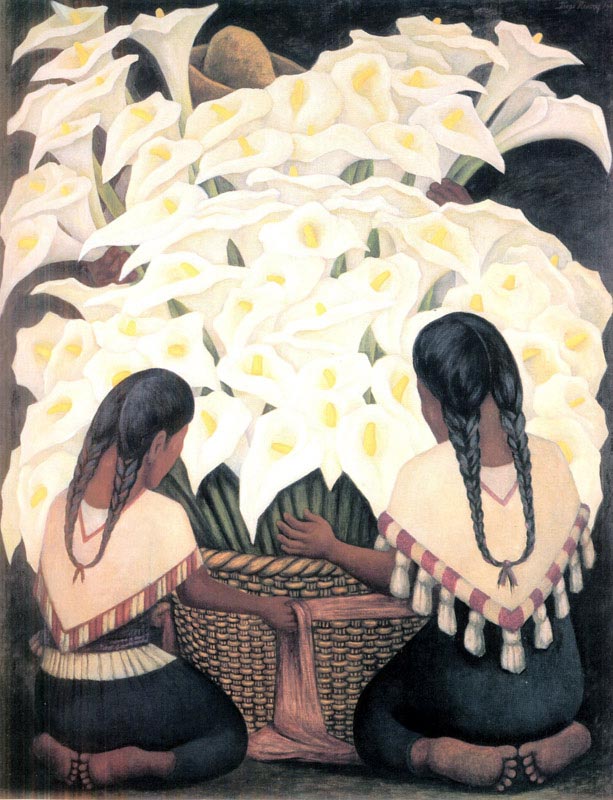

However, if for the traditional History « Latin America » has been functional as a geopolitical category, in the area of symbolic production its study, as a cultural unity based on the above mentioned identity topic, is an « easy to made » recipe which no longer works. The allegedly preponderance in the whole area of the costumbrismo and as well as political, social and surreal-fantastic themes, which allow the analysis of « Latin America » art as a homogeneous entity3, has been « (…) sterotypes easily assimilated and decodified by an exotic-hungry public and professionals of knowledge interested in pragmatical labelling or definitions »4 [my own translation from the Spanish]. The origin of this substantialist concept is in the nineteenth century, with the emergence of the new Latin American Republics, and was a part of a political, social and cultural project that sought the continental unity5. In the field of the visual production it is easily detectable in the nineteenth-century costumbrismo, and continues with particular intensity all over the first half of the twentieth century.

One of its peak moments is the widely known « Latin America’s first avant-garde », of which Mexican Muralism is a paradigmatic example.

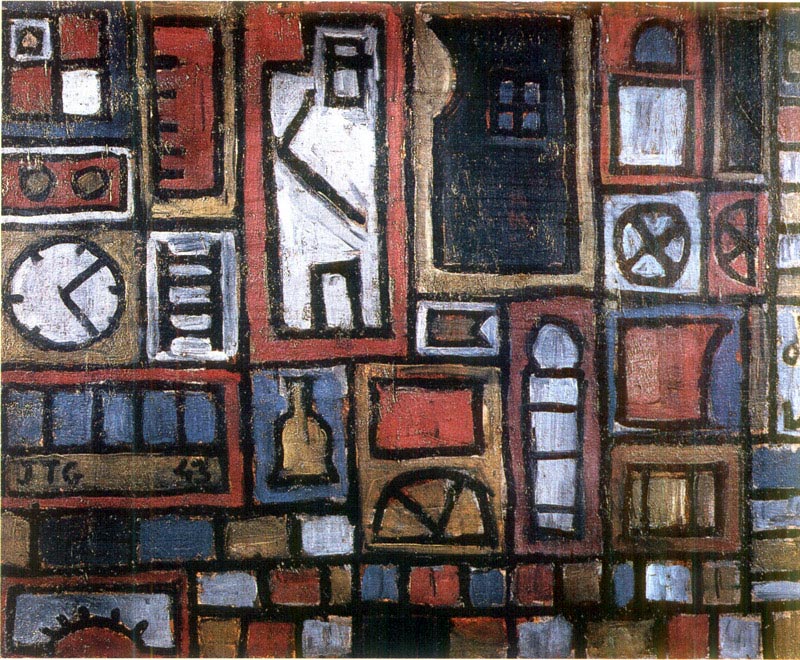

In visual terms, this scenario will begin to change between the 40’s and 50’s, with the irruption of the abstract styles in Latin America and the work of artists like Joaquín Torres García.

Even in the sixties, when it became evident a return to the socially – and politically –engaged art (for instance the post-revolutionary Cuban art and the Argentinean experience, Tucumán Arde), during the next decades the Latin American artistic scenario will be more complex and will begin to open a window for the arrival of the postmodernism.

« That abundance of themes but enhanced the plurality of the visual Latin-American universe on a worldwide scale and made even more difficult to define what has always been termed Latin American Arts. The widely believed monolithic character of our expressions (….) conflicted again with a never before seen plurality, that was not easily approached from the viewpoint of traditional historiography and critics. This widening of the Latin American visual arts opened new possibilities for curators and researchers of the New Continent (…) »6 [my own translation from the Spanish]

Unfortunately, the Latin American Art History bibliography, defined as « classic » has contributed to perpetuate the schematic vision of the Latin American artistic production.

An insufficient History

The definition of identities based on national boundaries or geographical notions, was widely used by the traditional bibliography about Latin American art but was not sufficient to comprehend the cultural behaviour of certain areas. We are talking about «in-between » zones, that can be easily located in a map, but that do not have the group of exclusive characteristics supposedly shared by all the cultures included in certain region; border zones, impossible to fix within the identity stereotypes established a priori. Without suitable tools to deal with the analysis of this phenomenon, the easiest solution was made: to omit all those spaces that simply « do not fit in » and the emergence of « strips of silence » in traditional historiography.

Thus, while Mexico, Brazil and Argentina were the three main protagonists in Latin American Art histories, the Central American space was repeatedly ignored. Central America is an area difficult to assess from the traditional points of view that try to encompass « the Latin American » as a homogenous unity. First of all, its behaviour as a region (in artistic and cultural terms) shows particulars that are sharply different from those of other continental countries, among these: a history marked by devastating natural events, poverty rates among the highest in Latin America and historical indifference of the governments toward the cultural institutions.

Concerning the institutional sphere, and in contrast to the majority of Latin American countries, Art Academies and Schools will not develop effectively in Central America until the twentieth century. As a result of this late process of institutionalization, modern languages will arrive in most Central American countries (as a whole) during the forties – and mainly, fifties – of the past twentieth century. This heterodox modernity was functional only at a visual level and not necessarily at the institutional level. In many cases, some of these nations arrive to modernity when other Latin American countries are experimenting with postmodernity. According to Virginia Perez-Ratton, the structures supporting the art development in the area are nowadays unstable, precarious, short-term, and always suffering from the intrusion of politics7.

On the other hand, Central America has imprecise boundaries, un-defined territories which traditional bibliography about Latin American Art History has contributed to preserve. In this regard, the area is studied mainly through the «great Central American paradigm»: Guatemala. Following in chronological order according to the aforesaid texts, are Honduras, El Salvador, Nicaragua and – in the eighties of the last century – Costa Rica were included in the analysis. However, countries like Panama and Belize are totally ignored or very seldom mentioned, sometimes classified among the Caribbean, sometimes included in the continental area.

At this point I would like to underline that when we talk about Latin American Art History «classic » bibliography, we are speaking of studies made during the sixties, seventies and the beginning of the eighties. In general, most of these texts show a lack of studies on Central American art. Some of them tentatively include the region through the analysis of certain countries of the area, but they are really insufficient. The first important attempt to open a window for the Central American art was Latin American Art of the Twentieth Century, by Edward Sullivan; but this text was written at the end of the nineties. Sullivan includes a more critical and deep study of the area, written by Central American specialists.

It is important to note that, starting from the 90’s, specialized bibliography on Central American art begins to be locally elaborated. At that moment, when the art of the isthmic America gets in contact with the postmodernism, emerge promotional strategies that try to compensate the lack of an adequate institutional framework. Regional artists begin to have an international outlook due to their inclusion in major events such as the Venice Biennial, where some of them will receive important awards.

The specialized bibliography about art, written by regional experts, mirrors the integrationist strategies of the nineties. All these authors share the same concept about Central America: Guatemala, Honduras, El Salvador, Nicaragua, Costa Rica and Panamá. Most recent sources include also Belize in this area.

Updating tools, completing History

In Latin American art and culture, Central America neither can be studied as a monolithic cultural entity. It is well known that resources of traditional art historiography, which often establish polarities, schematic differences and ignores the « contaminations » and multicultural dialogues, are not suited for the current study of the cultural field. Isthmic America not only changes over time and as a consequence of historical events, but also gets hybridized – from the cultural viewpoint – with other notions, such as Caribbean space (to which Belize and Panama are tightly associated). Furthermore, Central America expands its limits beyond its physical-geographical boundaries that situate this space in the middle and isthmic part of America, connecting the two large landmasses (North and South): the huge migration in the eighties, mainly to the United States, drew new limits.

Today the borders are re-designed on the basis of cultural parameters instead of spacing; therefore, the resources of traditional art historiography, full of substantialist concepts and geographic determinisms, are ineffectual for the study of Central American Art and, in general, of Latin American Art. As Román de la Campa said:

« (…) Defining the nation, perhaps the implicit task of the scholarly disciplines created by modernity, is no longer ruled by easily conceived propositions (…). Border zones, unrestrained illegal migration, the Internet, cable TV, the consumer’s citizenship and the ever expanding service industry (…) have transformed the play field (…) »8 [my own translation from the Spanish]

Overcoming the traditional study of Latin American art, particularly in certain academic circles, is imperative. The use of more updated resources to implement its analysis will open new areas of study, whose historical omission needs to be widely claimed, and therefore, will incorporate these areas effectively in the historiography of contemporary art.

Notes

[1] Santiago Castro-Gómez and Eduardo Mendieta. La translocalización discursiva de «Latinoamérica» en tiempos de la globalización. In: Teorías sin disciplina (latinoamericanismo, poscolonialidad y globalización en debate).

(http://www.duke.edu/~wmignolo/InteractiveCV/Publications/Teoriassindisciplina.pdf). (08/15/2011).

[2] Ibid.

[3] From the theoretical perspective, terms like «hybridism», «heterogeneity», «transculturation», «appropriation» and «resignification», became also stereotypes of the Latin American identity. Cf. Gerardo Mosquera. Contra el arte latinoamericano. (http://arte-nuevo.blogspot.com/2009/06/contra-el-arte-latinoamericano.html). (08/29/2011).

[4] Nelson Herrera Ysla. Una cierta movida en Latinoamérica. In: Coordenadas de Arte Contemporáneo. Havana, Arte Cubano Ediciones and Centro de Arte Contemporáneo Wifredo Lam, 2003, p. 97.

[5] We cannot forget that this nationalist project had two sides. One that placed territoriality and physical boundaries, as demarcation lines of the singular and different. Other, linked to the idea of a continental nationality (a sort of continuation of the colonial structures) in which the national borders were eliminated to create the «Latin American space”, characterized by the permanent dichotomy civilization – barbarism, described by Domingo Faustino Sarmiento.

Cf. Claudio Maíz. Nuevas cartografías simbólicas. Espacio, identidad y crisis en la ensayística de Manuel Ugarte.

(http://www.lehman.cuny.edu/ciberletras/v05/maiz.html). (4/06/08).

[6] Nelson Herrera Ysla. Op. Cit., p. 101.

[7] Cf. Virginia Pérez-Ratton.Centroamérica: cintura o corsé de América? En: Visiones del sector cultural en Centroamérica. San José, Ediciones AECI Cooperación para el desarrollo, Centro Cultural de España, 2000, pp.78-79.

[8] Román de la Campa. Nuevas cartografías latinoamericanas. Havana, Editorial Letras Cubanas, 2006, pp. 26-27.

Bibliographie

– Ades, Dawn, Arte en Iberoamerica 1820-1980, Turner, 1990.

– Castro-Gómez, Santiago et Eduardo Mendieta, La translocalización discursiva de «Latinoamérica » en tiempos de la globalización, dans Teorías sin disciplina (latinoamericanismo, poscolonialidad y globalización en debate), 2011, en ligne, <http://www.duke.edu/~wmignolo/InteractiveCV/Publications/Teoriassindisciplina.pdf>,

– De la Campa, Román, Nuevas cartografías latinoamericanas, Havana, Editorial Letras Cubanas, 2006.

– Gutiérrez, Ramón et Rodrigo Gutiérrez Viñuales, Historia del Arte en Iberoamérica, Lunwerg, 2000.

– Herrera Ysla, Nelson, Una cierta movida en Latinoamérica, dans Coordenadas de Arte Contemporáneo, Havana, Arte Cubano Ediciones and Centro de Arte Contemporáneo Wifredo Lam, 2003.

– Maíz, Claudio, Nuevas cartografías simbólicas. Espacio, identidad y crisis en la ensayística de Manuel Ugarte, 2008, en ligne, <http://www.lehman.cuny.edu/ciberletras/v05/maiz.html>.

– Mosquera, Gerardo, Contra el arte latinoamericano, en ligne, 2011,

<http://arte-nuevo.blogspot.com/2009/06/contra-el-arte-latinoamericano.html>

– Pérez-Ratton, Virginia, Centroamérica: ¿cintura o corsé de América?, dans Visiones del sector cultural en Centroamérica, San José, Ediciones AECI Cooperación para el desarrollo, Centro Cultural de España, 2000.

– Rojas Mix, Miguel, America Imaginaria, Barcelona, Editorial Lumen, 1992.

– Yepes, Enrique. América Latina, un concepto difuso y en constante revisión, 2011, en ligne, <http://www.colegioisc.cl/apuntes/4medio_america_latina.pdf>.