Connecting images: the sound induces a visual perception

I would like to start with a general thought regarding the concept of composition. This organises all of the levels, be they visual or auditory, of your soundtracks, films or installations. Could you talk about this notion in your practice?

I’ve always felt that despite being a sound creative the emphasis on the visual always maintains a presence, even in performances that are purely about sound in and of itself. It’s easy to speak of sound being visual, cinematic, suggestive, imaginary, but when I create work it’s almost exclusively sonic, about the ears, about the immersive, physical and emotive experience of sound.

There is always a moment in any new work where you are presented with a blank page and need to make your mark on it. That can sometimes be rather intimidating but I simply begin with something, which often might be erased later on, but you always need a place to start. Compositions are born sometimes from the most surprising of places. I have kept a diary since I was 12 years old, never missing a day, and equally a series of notebooks capturing countless (and frequently unfulfilled) projects, ideas, propositions and structures. Every now and then I draw on these towards something new.

At the same time it’s worth considering the value of instinct and the element of the subconscious. I recently dreamt the title of my first new studio album in over six years. A word appeared that I wrote down on a note pad whilst asleep, which will form the artwork for this new recording. Sometimes sounds, shapes and structures appear in a similar manner. There is still magic to be found in the profoundly mundane moments.

In this moment on the electronic scene, according to me, there are two tendencies: an internal organic line in which the materials are organized in order to outline a narrative fabric; on the other hand, an external organic line in which the materials operate towards abstraction. Nevertheless, the two layers above mentioned (the sound and the visual) are not opposed to each other, but they’re both inscribed in a system of shades. Could you speak, in your work, about the tension between these two dimensions?

Any active artistic creative process is in a constant state of flux, combing personal issues of creativity moulded with technological advances, influences of peer groups and historical lineage.

For my own work there is a combination of the imagined and the unanticipated in any creative process. One can only try to project an outcome in any production but it rarely reveals itself in the very self same manner, often only merely touching on the ambition. Narrative has always played a key role in my projects — maintaining a line of continuity, even at the most abstract moments of improvisation, where a singular sound may envelop a rhythmic shape, is essential to the strength of my creations. Sound and visuals need to share a similar route, the same language, not divide the eye and the ear.

Yours live sets dissipates a well-known misunderstanding, that brought on by the argument about the quality and nature of the relationship between sound and image, for example in yours 52 spaces (2002) in relation with the movie The Eclips (1962) by Michelangelo Antonioni. In areas such as those of sound installation and video arts, the misunderstanding arises when the artist thinks he can create an artwork by simply laying together images and sounds. Your interventions are a very interesting example of an integration and resonance between image and sound. Could you speak about this aspect of the question?

Issues of sight and sound, especially the use of imagery and projections in the role of performance in electronic composition, suggest a deeply complex and contemplative act. Many artists seem to consider the use of visuals as a replacement for the physicality of the theatrical act of performance, since many electronic performances exhibit the same static qualities. Commonly a solitary figure stands behind a computer on a stage and presents their work, motionless, inert, fixed to the stage. The use of any visuals clearly acts as a distraction but can also easily mislead and confuse the viewer. In addition it has become fashionable to simply use an old silent black and white movie or some other abstract visuals that merely occur at the same time, offering no relationship or narrative to the soundtrack itself. These occasions may offer an idea of chance and causality when at points the image and sound converge but for my own performances it has become vital that the integration is perceptible and meaningful. A story can be told in many ways but a closer rapport and bond between the audible and the visual can successfully alter a performance in extremely significant and often subtle ways. I have been the unfortunate witness to performances where images have subsumed the sound too, so that one cannot listen without the distraction of images and light.

Commissioned by The British School at Rome for film director Michelangelo Antonioni’s 90th birthday in 2002, my own project 52 Spaces uses sounds of the city of Rome and elements of his movie The Eclipse (1962) to create a soundtrack of an image of a city suspended in time, anonymous and surreal. A defining cinematic figure of the 1960s and 1970s with his movies Blowup (1966) and Zabriskie Point (1970), Antonioni’s films explore the tiny details of our lives in intimate, intricate ways.

To accompany this soundtrack I chose the closing 52 images of the film, 52 scenes where the camera searches for the characters in the story but cannot locate them. Instead the viewer experiences empty distant spaces, Rome framed in another light. I slowed these down to a kind of mnemonic slide show and accompanied them by audio culled from the movie processed with elements from the soundtrack’s original melody, conveying a complex and mysterious chronicle, offering up a space for contemplation and reflection as the soundtrack weaves an imaginary narrative. Each scene features tiny details of sound synched to the image, often very modestly – footsteps of a passing nurse, water falling from a pipe, brakes on a bus, alongside more abstract passages of sound, so it is clear that the sound is mapping the image in an intelligent and sensitive manner. It’s almost as if you are gently floating through the city, experiencing this dream-like state.

The Matter of the sounds and voices

Your works are based on the meticulous process of reduction. According to me, your vision is concentrated on the molecular structure of the sound, the radiography of a sound (your name, Scanner, is in this direction, according to me). Please, could you speak about this aspect, about material dimension of a sound in your works?

I am very clearly a reductionist. Having begun my recording career when I was a mere teenager, using cassettes and reel-to-reel recorders an economy of sound was essential, in fact there was no other opportunity. When I moved into using early sampling techniques, even the very first Scanner CD (1992) I only had access to a four track tape recorder and an effects unit that allowed me to randomly loop any sounds, slow them down, speed them up, but never store them in any permanent manner. My approach was to embrace the present, the opportunity of the moment. Taking this idea forward into using computer technology I tend to spend a great deal of time removing sounds, subtracting, trying to locate the “truth” of a work beneath the surface. It is very easy to be drawn to a point of saturation with music software, where one adds layer to layer until the work itself is lost to an abandonment of samples and sounds, where the target is obscured. Clarity can be found through the most minimum of means. The material dimension plays a large part in the construction of my works and I often use software like Native Instruments Reaktor to investigate into the grains of a sound, the zeros and ones, delving into the particles and granules that combined produce this field of sound. Drawing on sounds that are around us but exploring the particles themselves that make up their sonic structure has always appealed to me, expanding, contracting, looking inside their make up. Searching inside the most banal commonplace sounds for that which intrigues is always the greatest challenge!

It seems to be, in your work, the predominance of a « latency » of the sound. What emerges here is a subliminal dimension of sound organized by the intervention of the different frequencies. In this sense, you materialize the frequencies in giving an almost tactile character to your sound. Could you talk about a physical dimension of a sound in your work for example in Surface Noise (2001) or in a live set?

An interesting idea that has always appealed to me since I was a teenager was the projection of sound into shape, so one could create a shape in space just using sound. I remember dialoguing with friends at a young age wondering how it might be possible to suggest a series of circular stone loops in sound, or a triangle for example, one of those pretentious adolescent moments of discovery. Further on I became interested in the physicality of sound, not a brutal force as in the work of artists such as Throbbing Gristle or Pan Sonic, but the relationship between the frequencies in the music, using them in a painterly way, or perhaps even sculptural manner, to offer them a surface.

From the earliest Scanner CDs in 1993 and 1994 I was interested in the sound spaces around us. On these releases I pushed towards using cellular communications and their accompanying noise and feedback in a musical format. Sometimes the high frequency of cellular noise would pervade the atmosphere, at other junctures it would erupt into words and melt down to radio hiss. Intercepted in the data stream, transmissions would blend, blurring the voices and rupturing the light, creating audio transparencies of dreamy, cool ambience.

Later releases like Spore (1995) and Radiance (1995) dealt with a more emotive textural approach, shifting the focus from the voice to the atmosphere.

In this way you are constantly seeking a physics of the sound, perception level of a sounds, of the variation created by relation between sound and silence. In other words, this is the definition of an inaudible background texture that makes the audible stand out and be perceived, for example in Radiance or in Atavistic Endeavour (2004), in collaboration with Kim Cascone. Could you speak about this ephemeral dimension in your composition between audible and inaudible?

I have always been interested in the backgrounds of paintings and photographs; elements that do not take the focus of the eye immediately yet assist in conjuring up the total impact of an image. It is similar with my relationship to sound, where frequently it is the spaces in between as well as the almost imperceptible shifts in tonality and frequency that make up the whole colour of a production. Space in works offers contemplation and moments for the ambience itself, the location where you are actually listening, to take priority too. I have thrived on an aspect of recording production today where it’s impossible to imagine where in fact the listener will be enjoying this work later on. The location of the receiver can have a real impact on the narrative and musicality of a work you produce but there is simply no way to predict this outcome. This ephemeral quality in some of my works reflects this out of focus shift, blurring the lines between the heard and the imagined, where the listener takes some responsibility for the actual reception of the work itself and therefore its interpretation and ultimately the success of the recording.

I am interested, in your work, to the « organic » dimension of the sound materials. I think about the voice, for example. Could you speak of the « voice-material » in your composition, I think to The garden is full of metal (1997) for example.

Back in my unwieldy teenage years I had a chance encounter with a neighbor’s Ham Radio, an early form of radio communication favored by truckers on the road long before cellular telephones, which meant that often when I listened to records or the radio at home, their voices would feature as uninvited guests with my amplifier acting as a receiver for their banal communications. These conversations became a common ghostly presence within my field of sound and combined with my eclectic listening habits of the time—Throbbing Gristle, John Cage, Brian Eno and David Byrne and Robert Fripp—led to the first of several Scanner CD recordings on Ash International in 1992. Intercepting cellular phone conversations of unsuspecting talkers and editing them into minimalist musical settings as if they were instruments, brought into focus complex issues of privacy and the dichotomy between the public and the private spectrum. Sometimes the high frequency of cellular noise would pervade the atmosphere, at other junctures erupt into words and melt down to radio hiss. Intercepting the data stream, transmissions would blend, blurring the voices and rupturing the light, creating audio transparencies of dreamy, cool ambience.

In particular the live improvised aspect, having no anticipation where the conversation would turn next, what would be revealed next, the sudden changes in a flash, have clearly reflected upon my work these days too, and the nature of my life performances today follow this trajectory in that they are never finished. The performances are of that moment, not to be repeated, and that’s very important to my work. Using these scanned “found” voices in my work at the time was also a rare opportunity to record experience and highlight the threads of desire and interior narrative that we weave into our everyday lives, to explore the invisible, the ghostly presence’s all around us but impossible to pinpoint, and most especially a way of humanising the experience of experimental music, of combining the very real and banal with another level of contemplation.

I was also always intrigued by Electronic voice phenomena (EVP) too which were first discovered by the Swedish artist Friedrich Jürgenson in 1959. Jürgenson was recording birdsong using a reel-to-reel tape recorder and when he replayed the tapes, he heard faint but intelligible voices in the background, even though there was no-one else in the vicinity when the recordings were made. By repeating the procedure, Jürgenson found that the voice recordings could be reliably replicated. Latvian writer and intellectual Raudive followed in this tradition and was an inspiration to my use of voices buried under the surface of my recordings too, emerging from a sonic ambience that is viral, meshed, conspiratorial, dank, introverted, and organic.

The Jarman recordings were a very more personal project, a tribute in a very intimate way to a figure that personally inspired me and was a friend of mine up until his death. Within the electronic datascape that my work inhabits I still like to use the human voice for its physical presence. Even if the language, the meaning, the accent or the narrative is not understood it is the telepresence of this disembodied voice that can still carry a special resonance for us. The voice still acts a fleshy transmissive virus that we can all relate to, creating a sound language that relates to our own natural system. The “ghostly” voices on these works still have the ability to move, to emote, to throw up all manner of images through sound and our own imaginations that no other form has the ability to do.

At different levels, in your composition process is a same “modulation time phenomena”. The sound – or the form of time – is pulsated, is fragmentised; there is a superposition of a different sound’s surfaces at varying speed (acceleration, loop). In other part of the work (or in others works) the sound is not pulsated, but is modulated, in perpetual movement as a wave, it’s a “duration”. Therefore to think the sound as an aesthetic of the time, in which the time takes form, even if unstable… could you speak about your idea of the “time” in the sound composition?

Time can be an infinitely complex concept to grasp. I employ sounds in a sculptural way, especially within a live context, developing open frame narratives, pieces that offer no clear beginning or end, but address a layering of sonic artefacts. In performance in particular I am keen to create a very inviting immersive space, one that seduces the listener, draws them in, but does not contain traditional patterns of song followed by song, but one mesmeric spell that begins and ends at a point only decided once this is in process. Some recording, Sulphur (1994) for example present the context of a live concert, sheets of sound laid upon one another, almost as types of film, with voices scanned live, all captured live, so impossible to gauge which way the performance will turn. As such time has often been impossible to measure in these contexts.

Around the listening: redefine the perception

The redefinition of the notion of the listen in your works, brings me to speak of an immersion in the sound. This immersion has a meditative character: the body is inside the sound. The body of whom listens he is crossed by the sound, one way to explore our loneliness … Could you speak of this aspect about the strategies for a listen redefinition?

Immersion in sound for me is essential, in recording, installation and performance. I’ve always had a curiosity about the way we listen to sound, how we digest it through iPods, headphones and speakers and how the environment around us can have such an affect upon us and what we are listening to. Wondering where the lines dividing the actual listening experience and the source itself – CD, iPod, etc – meet and cross influences even how I compose and produce music. Listening on headphones in particular establishes an immediate relationship to the body itself, displacing the imagination and physicality of the body.

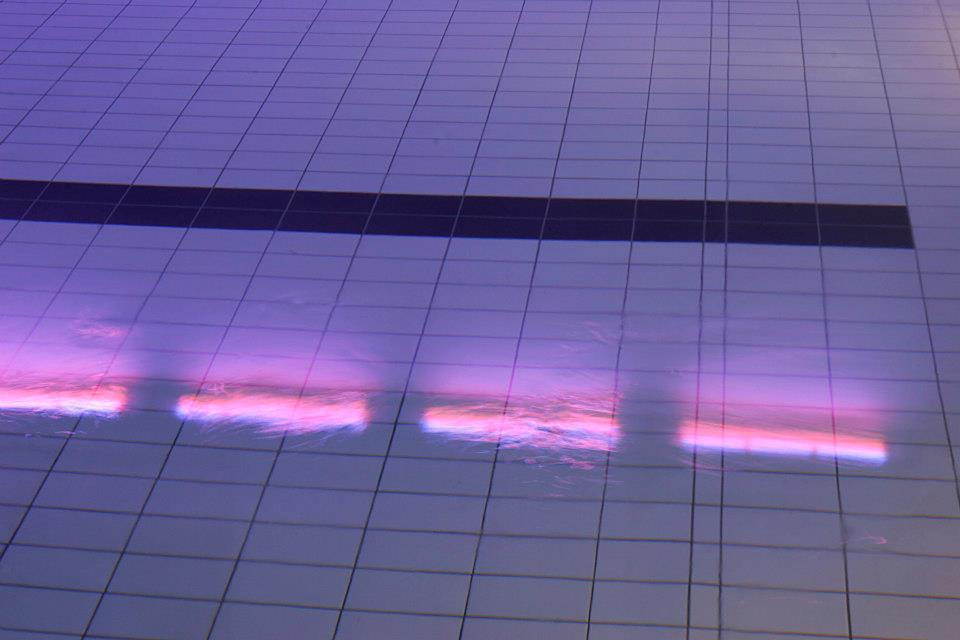

I produced a work in a hospital in Sunderland UK, Turning Light (2007) for Walkergate Park, This is one of the most advanced units of its kind in Europe. It offers comprehensive, highly specialist services for people with neurological conditions, such as head injury, multiple sclerosis, stroke, Huntington’s disease, Parkinson’s disease, dystonia and motor neurone disease. “Turning Light” utilized the benefits of sound and light in physical and emotional therapy within the hydrotherapy pool. Vibrant LED lights produced a field of colour across the space, complimenting the ambient sound, encouraging a healthy balance and harmony in both patients and staff working in the pool area, creating a positive energy in a functional space. Certain frequencies can help achieve relaxation, lower blood pressure and alleviation of physical pain or injury, leading towards a greater sense of well-being and inner content. Here the sound could offer something beyond simply entertainment towards a healing process.

In this context, according to me, the colour is an important element in your principle of composition. If I think to Ricochet (2007) also in Turning Light or in Falling Forward(2010). Could you speak about this element in these works?

It’s an interesting juncture to consider colour as much of the sound I produce I would consider as black and white, yet sometimes the richness of colour breaks through this monographic texture.

In Falling Forward for example the work explodes the idea of time and presence. Filmed in extreme slow motion it offers suggestion of a presence passing the camera, as if the spectator is looking through a window onto an event happening in real time, but the richly colourful background is simply a highly enlarged iPhone photo of a New York City building.

Most of the foreground action is in black and white, so images of broken ice, glass, photographs and dust pass by in strong contrast to this richly colourful background.

Like much of my musical composition I place a lot of emphasis on contrast, so volumes can radically shift in a performance or recording, sometimes almost disappearing.

Logic of collaborations

The logic of a collaboration is an important aspect in your production. Could you speak about the points of connection in your collaboration with Olga Mink, in Atlantida(2009) composed with Olga Mink or – in a same logic – in Empac-onedotzero (2009)?

And as such my relationship with composing for dance began. Since this time I have frequently collaborated with choreographers in the development of new works, in particular with the British choreographer Wayne McGregor or with the filmmaker Olga Mink. The relationship between us is invaluable. I am a consistent collaborator in all fields, often with artists quite outside of the field of music. Whether it’s with a writer, a DJ, a video maker, a choreographer

or architect, the ability to exchange and share ideas is crucial and these collaborations allow me and the collaborator to work as both negatives and positives of each other, recognising spaces within the work fields and ideas of the other. It teaches the respect of space but also the relevance of context and extension of ones ideas to the other.

I have always had what one might consider a very rudimentary approach to my working method, that is to try and only work with people I like in situations that I enjoy. I work on projects that I am interested in, nor for commercial or financial reasons. I feel that my approach is chameleon-like enough that I can shift within my structure to engage on many different levels within a project, describing myself at times as the “risk factor” because I cannot offer any expectations or guarantees but if one demonstrates a trust in a relationship then this I believe will be fulfilled in countless ways. I’ve been fortuitous enough to combine forces with some key figures in dance, music and art that have shown a trust and understanding in what I have to offer. What more could one ask for?

Another important collaboration concerning the relation with Wayne McGregor | Random Dance. Could you speak of the ideas that have tied you with McGregor, of the relationship, particularly, between the sound composition and choreography?

Curiously I never intentionally ever composed music for contemporary dance until up around 1996, but was conscious that dancers and choreographers had been using my CDs in rehearsals and performance, as the works themselves had expressed a suggestive motion and sense of architectural space, a liberal entry into new movement.

With Wayne McGregor we have established a working relationship where we establish as far as possible the underlying themes of a work. He will often play me works from other artists that present a mood or texture, a tension or drama. This helps as a guide to sculpting the shape that the final work should take, though a stout sense of trust is implicated to offer me the freedom to disregard theses guidelines as much as concede to them. Mostly I occupy the position amusingly known as “the risk factor” where the commissioner does not have particular expectations for a project, more an awareness of the thrill of the unknown! Wayne is always keen to explore new technologies, advances in brain research, costume materials and design and has a very sympathetic view towards contemporary music and composition. It helps that he reads music too.

More recently through the invitation of Wayne McGregor this relationship has blossomed to a new creative level. Having previously make use of my music to accompany his work Detritus for the Rambert Dance Company, we met to consider the possibilities of developing a new work, Nemesis. McGregor’s work appealed to me as he has historically been presenting a vibrant form of dance that embraced new technologies.

For our collaborative work Nemesis the mood shifts between scattering beats and warm seductive strings, melancholic melodies and pixellated abstraction. At just over one hour long the work captures the image of dance in sound, the sad, unravelling love duet set in a green-lit, empty foyer, the woman’s hallucinatory solo in a church, the lost figures, an eerie, glamorous species, part insect, part warrior, shuffling across the floors. Having worked alone in my studio to create this soundtrack and only viewing still photographs of insectoid shapes, blurred still images of industrial spaces, the final work took on an entirely clear lease of life in performance. In collaboration with the lighting and digital projections that accompany the work we were able I feel to evoke a mood that is more than the movement of the dancers, that intricately wove a relationship between the art forms. What struck me as extraordinary in the work was this close relationship established between the collaborators, creating a work that explores the relationship between body, screen and machine, a type of extraterrestrial dance meets reality TV.

In this sense, could you speak about your actual collaboration with the Italian theatre company Lenz Rifrazioni for a stage work about King Lear (2015)?

This is a continuation of a collaborative process that has continued over some years as we’ve previously worked on projects together. Here it began at an unfortunately and extremely tough time for me personally since my brother was diagnosed with terminal cancer at the origin of this project and hence my initial input was a process of recycling past materials in the hope that they might work contextually with the framework of the theatrical work.

After his passing within a very short time I returned to the project, which was to be based around the songs of Verdi, considering it was to be premiered for Festival Verdi in Parma. Francesco Pititto of Lenz Fondazione picked out particular arias, and I reworked these in a variety of ways, sometimes replaying piano parts, sometimes reimagining them in new string arrangements or treating and processing archive recordings, which has led to a full score delivered in two halls at the same time, so the audience themselves move between rooms during the event, literally swapping at the interval.

Toward which direction is developing your new creations?

The role of live performance in my own work became more questionable in recent years so I’ve stepped away from much of that and focus more on commissioned works and collaborations. Having recently moved out of London for the first time in my life to a former textile factory, for the time being I’m concentrating on setting up a recording studio and office there as well as an artist residency programme and a foundation for arts to support younger artists.

In addition I’ve devised a TV show that will be seen internationally in 2016 exploring how we listen, share and pass music from one generation to another. I continue to be delighted by the surprise routes that my own life and work seem to take!