This paper focuses on a workshop on immersive performance that ran from January 7th until January 27th 2013 at the Curtis R. Priem Experimental Media and Performing Arts Center (EMPAC) in New York. The workshop was conducted by Eric Joris and his company, CREW. Since 1998, the immersive live art of this Brussels-based performance group has successfully challenged common notions of acting, (tele)presence, spectatorship, theatricality and narration. Scientific reflection has always played a role in CREW’s creative process, and engineers from different universities have developed new technologies for CREW to use on stage. The developers, for their part, reciprocally found in CREW’s experimental theatre a laboratory for testing the progress and feasibility of their interface designs.

In New York, CREW tested the possibilities of fusing footage taken on the spot with material that director Eric Joris recorded with his 360° camera in Japan shortly after the Fukushima nuclear catastrophe. The material from Japan was subsequently built into an artistic immersive environment, where an “actor” guides a “spectator” in the middle of the devastated areas, where debris is being cleaned away and where phantom cities and villages are being dismantled and reconstructed. CREW thus created an integrated perspective through reenacting a radical foreign experience in the current conditions of New York, as exemplary global village. The medium through which this attempt was enacted is the so-called HeadSwap technology. This interactive collaborative experiment extends individual experience towards the exchange of visual perception. Through the use of omni-directional cameras and head-mounted displays, the participants–both actors and spectators–can freely look around in each other’s environments, cognitively mapping each other’ s bodies as they move along. I will provide an account of the ways in which this artistic experiment, through the use of immersive interface technologies, blurs the traditional boundaries between the actor and the spectator.

This paper reports on a workshop in immersive performance that ran from January 7th until January 27th2013 at the Curtis R. Priem Experimental Media and Performing Arts Center (EMPAC) in New York. The workshop was conducted by Eric Joris and his company CREW, a performance group and multidisciplinary team of artists and researchers. Since 1998, the immersive live art of this Brussels-based team has successfully challenged common notions of acting, (tele)presence, spectatorship, theatricality and narration. Scientific reflection plays a constitutive role in CREW’s creative process, as since its inception, engineers from different universities developed new technologies for the company to use on stage. For their part, the technical developers found in CREW’s experimental theater a laboratory where they could test the progress and feasibility of their interface designs.

In New York, CREW embarked on a multifaceted project. The team wanted to test the possibilities of fusing footage taken on the spot in the working spaces of EMPAC with material that director Eric Joris had previously recorded with his 360° camera in Japan, shortly after the Fukushima nuclear catastrophe. The material from Japan was subsequently built into an artistic immersive environment where an “actor” guides a “spectator” in the middle of the devastated areas. CREW thus created an integrated perspective through re-enacting a radical foreign experience in the current conditions of New York, as exemplary global village. The medium through which this attempt was enacted was called the Head-Swap technology. This text provides an account of the ways in which this artistic experiment, through the use of immersive interface technologies, blurs the traditional boundaries between the actor and the spectator.

The experiment, to which EMPAC most generously invited us, was aimed at exploring the potentialities and limits of immersive performance. Accordingly, in this essay I will try to clarify these conditions by putting into perspective the goals, objectives and outcomes of our workshop at EMPAC. As with most projects on the borders of art and science, where practice-based theory is written, clear distinctions between inside and outside become blurred. My own position as a writer is part of this confusion. As a performance theory scholar I have been working with CREW on different projects since 1998. I have become enmeshed in their practice, co-elaborating the design and the dramaturgy of Joris’s creations. More often than not, my involvement has included writing texts trying to provide a vocabulary and a context in order to better grasp and describe CREW’s theatrical experiments with digital media. Some of those texts served the group, others were discarded, and yet others were published in academic contexts to document CREW’s development in intermedial performance art. “Immersion” was often the key word. For reasons that will become apparent, over the years “Live Art / Live Media” became the motto under which the performances were produced.

Living in Plural

“It’s a sort of lucid dreaming,” one of the spectators exclaimed during a rehearsal, while the assistant was busy removing his body harness. The person had kept the video goggles, digital screens, wires and cameras in place for the last thirty minutes. This was the duration our test person had spent actively walking a square matrix while visually immersed in a surround video environment that took him elsewhere. We had drawn the grid on the floor of one of the workshop spaces at EMPAC, Troy, just two hours north of New York City, up the Hudson River. The grid measured no more than ten square meters. Paradoxically, however, the spectator at the same time had been walking through a desolate Asian landscape that apparently had suffered catastrophic debris flows, with houses washed away by sudden flood. He witnessed this unusual, eerie yet meditative environment through the goggles and earphones of a head-mounted display. The experience of “being there,” wandering through the remains of what once seemed to have been an inhabited site while simultaneously walking a square in the workshop space, was enhanced by a highly responsive motion tracking system. This system adjusted the visual landscape according to the movements of his head. As a consequence, he was able to physically move and walk around within the video-captured landscape of what later turned out to be Sendai, the capital city of Miyagi Prefecture, Japan.

On March 11th 2011, the largest earthquake recorded in Japan’s history and a subsequent major tsunami destroyed the coastal area of Sendai, killing hundreds, and injuring and making homeless countless more. The fifteen-metre tsunami disabled the power supply and cooling of three nuclear reactors, causing a nuclear disaster. During the CREW performance, the spectator walked this ghost land that remained after the water receded. No wonder that, while the assistant was busy disentangling his physical body from the virtual one, it took him some time to readjust and to return to Troy in the winter of 2013. His senses were recovering from the negotiation between his physical self and the visual imagery, between what he knew was New York, but what his senses convinced him to be Japan. “It’s definitely a disconnection,” he knew, “it’s like, sometimes you’re dreaming and then you’re like ‘oh my gosh, I’m dreaming!’, and then you can sort of control your dream a little bit, and then you forget again. Then the seeing yourself part comes back to you again. I know that’s me, but let me check: ‘Are those my shoes, is that my shirt?’”

The technology that makes possible this shifting between two worlds is unique. Working in the epicentre of technological developments, CREW more specifically has acquired a privileged position in exploring and developing the language of omni-directional video (ODV). ODV is a new immersive surround video system, developed for the company in collaboration with Eric Joris by the Expertise Centre for Digital Media, University of Hasselt, Belgium (EDM/HU) and expanded within European research programs on immersive media and digital technologies. The system allows the spectator a surround video display through a head-mounted display. Equipped with an orientation tracker, this display shows a panoramic video that corresponds with the spectator’s view, direction and desired field of view. The technology thus places the viewer physically in a video-captured surrounding imagery, generating a very lively environment. Consequently, the filmed image becomes a space in which the viewer can dwell. By mixing real and virtual experiences in novel ways, this technology offers the possibility to extend the traditional categories of experience. The virtual space coincides with the participant’s embodied own space, integrating thus the performance itself along with the eventual scenery and actors into the physically perceived world of the spectator, installing a new intimacy and a high degree of presence. By using digital immersive technology, the performances thus intermingle three levels of immediacy and presence: the real time presence of the actors and the spectators (1), prerecorded images (2), and metadata such as text material or even digital avatars embedded in the overall spatiality and action pattern (3). Eric Joris has been optimizing this technology, developing it into a performative tool since he first started implementing it in Crash, a performance in collaboration with the Belgian writer Peter Verhelst and staged in the Toneelhuis in Antwerp in 2004. “Je est un autre” was the theater critic Geert Sels’ conclusion in his review of this show in the city’s leading newspaper, De Standaard1.

The immersive walk-through experienced by the spectator in EMPAC gave way to a more radical experiment that Eric Joris with CREW conducted in the same space during the following weeks in January 2013. The goal of this workshop was to create, through experimental immersive technology, a collaborative interactive experiment that would extend individual experience by “exchanging” visual perception. Our spectator, in other words, would not remain alone in the virtual desert of the real. Soon his perspective would be integrated and exchanged with the viewpoint of another person present in the same environment. The medium through which we wanted to attempt this enactment was what Eric Joris termed the Head-Swap. Through the use of omni-directional cameras and head-mounted displays, two participants would be able to “trade heads” – to freely move around in each other’s field of vision, cognitively mapping the shared environment and each other’s body as they moved along. In other words, the Head-Swap would take the experience one step further by creating a collaborative interactive performance with two people in the same immersive space.

Initially, the Head-Swap was an interactive performative experiment that served as a test – a responsive environment for experimentation – allowing to field-test the goals set by the European IP project 2020 3D Media. In March 2008, this large-scale project started the research and development of creative forms of interactive, immersive and very high quality media (such as 3D, virtual and augmented reality), as well as new forms of experiences for individual users based on omni-directional or surround video. The European Research Consortium consisted of sixteen participating organizations, among them academic research institutes, such as the Heinrich Herz institute in Berlin, CREW’s partner EDM / HU, and some of Europe’s most prominent manufacturers of digital film cameras, projectors, and recording and playback systems. Also included were manufacturers of post-production and audio equipment, and programmers, together with media production and media distribution companies. As an artistic company in a consortium of industrial and academic partners, CREW was in charge of the realization of the empirical research into aspects of presence, narratives and spectatorship in film-based 3D immersive environments, a domain in which this collective has acquired a unique expertise through the creation of their immersive performances. Being of dual origin – scientific and artistic – the Head-Swap is typical of the working process of CREW. More concretely, two spectators in different geographic locations (Barcelona in Spain and Mons in Belgium) were equipped with an HMD and an omni-directional camera. They exchanged and moved around in each other’s fields of vision: spectator A viewed and manipulated the footage filmed by the camera on B, and vice-versa. The two people would talk to each other via microphones and headphones, and they would have to perform by sustaining each other. Both could, in other words, move around freely. They would have to find their way through a building or through public space, depending on each other’s instructions. Put differently, they (re)constructed the conditions of theatricality by cognitively mapping each other’s movements. This real-time confrontation with the digital interface created a highly intense experience that forces the spectator to question her trust in her own senses.

What happens here is confusion between one’s own body-image, both on a visual and on a tactile level, and a body-image that belongs to someone else–a body-image that is technologically mediated. This is also known as an out-of-body experience. And indeed, at different points in the repetition process of CREW performances, when trying out the environment itself, we experienced out-of-body sensations. We felt a body that was outside of ourselves as if it were our own body. This might sound mystical at first. However, it was only after some time that the artists in the theater of CREW found out that scientists were performing exactly the same experiment in their labs. This phenomenon is known as “the rubber-hand illusion,” and has been extensively investigated by cognitive neurologists. In this scientific experiment, the sight of brushing a rubber hand at the same time as brushing the person’s own hidden hand has proved to be sufficient to produce a feeling of ownership of the fake hand. (Botvinick, 1998, p. 756) In a similar way, the Head-Swap took the immersive theater to a next level, where the performance transformed from a one-on-one performance into a communal space visited by more people. The status of the spectator in this performance is further complicated. His presence not only merges with the presence of the actor inhabiting the virtual environment. Through the immersive system he can now see and even experience the bodies of other spectators in the same environment.

The consequences for our definition of both actor and spectator are crucial. In Mapping Intermediality in Theater and Performance, Robin Nelson proposed the term “experiencer,” where audience or even “spect-actor” (Boal) were no longer adequate to express the situation:

It suggests a more immersive engagement in which the principles of composition of the piece create an environment designed to elicit a broadly visceral, sensual encounter, as distinct from conventional theatrical, concert or art gallery architectures which are constructed to draw primarily upon one of the sense organs – eyes (spectator) or ears (audience)(Nelson et Vanhoutte, 2010, p. 45)

While this suggestion focuses on the move from the eye to the other senses, it does not sufficiently account for the ways in which this mode of sensory perception is deeply imbricated in myriads of forms of technology, agency and their spatial arrangements. The performance in EMPAC, by not only using pre-existing documentary material but by actually also performing this material, necessitates the definition of a new relationship between acting and spectating or experiencing. In the remainder of this paper, I would like to reconnect to the rhetoric of walking, to demonstrate how space perception and perspective are key to our understanding of the characteristics of CREW’s performance and to our notion of the actor.

Walking Reveries

By referring to the state of “lucid dreaming,” the intuitive exclamation of our engineer hit the nail on the head. Indeed, immersive experience is often linked to a dream-like state. In “Telematic Dreaming” Paul Sermon famously turned a bed into a support of high-resolution images that show a partner, intimately present yet far away. The installation functioned as customized video-conferencing systems with the inserted bed like a mirror that reflects one person within another person’s reflection. According to Oliver Grau, this techno-aesthetic language left a “sensory impression achieved synaesthetically where hand and eye fuse.” (Grau, 2003, p. 275) Although one person was not “really” touching the other, the image of another body in close proximity had such an impact that the visual impression suggested tactility and intimacy. The crux of this deliberate play with tele-presence is in the use of quotation marks used to set off reality. The real is postponed yet embodied, as in a dream where mental and material images and feelings are so ambiguously related to one another that their respective contributions are difficult to separate. In a metaphorical way, the punctuation marks sum up the historic tension that performance has with asynchronous engagement, especially with digital technologies blurring the lines between what was once considered live and mediated. Auslander vs. Phelan has been central to this debate, which has its origins in the field of performance studies in the 1990s. However, in light of recent and rapid developments in media technology, it might be time to rethink the key terms and issues in that debate. Over the course of our workshop, we did indeed find that an updated approach is needed for our conceptions of how virtual and material spaces interact.

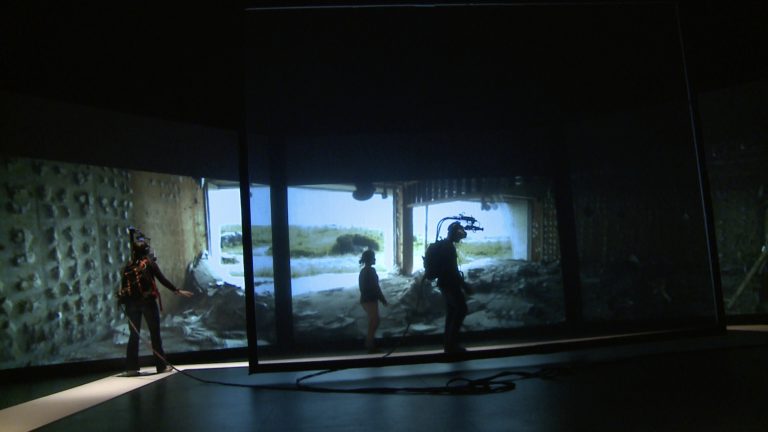

The material from Japan was built into an artistic immersive environment that puts the spectator in the middle of the devastated areas of Sendai, where debris is being cleaned away and a phantom city is being dismantled, to be reconstructed in the future. Eventually, the walkers’ intertwined paths weave the material and virtual spaces together, and give shape to a layered landscape. Moreover, this landscape with “experiencers” would not fold back upon itself, but would be staged in front of an audience that would be witnessing the intersecting trajectories. Viewed in this perspective, the immersive scenery, participants included, would be embedded in a regular stage perspective. Four panoramic screens show the scenery the participants see and walk in through their goggles, providing in real-time an exact image of what each of the “immersants” is witnessing. Furthermore, a tiny camera mounted to the headset of the participants switches to this physical environment as soon as they coincidently leave the delineated path. The interlocking of the virtual and the real, then, is far too complex to be translated into a clear partition between true perception and false delusion. Nor does the distinction between actor and onlooker seem relevant any more, since both constantly switch roles, to the point of being indistinguishable. As a consequence, some key terms and issues in the debate need to be revisited and scrutinized. Future research into this field might profit from an interdisciplinary approach combining different insights from various academic disciplines, thus avoiding some of the most obvious epistemological traps such as the ontological distinction between theater, public space and new media2. In terms of experience and spectatorship, the easy distinction between acting and spectating might perhaps apply to environments generated in the digital laboratories of virtual reality researchers, where, more often than not, graphics retain artificial qualities and the related images remain distinctly recognizable as belonging to a fictitious sphere. The surroundings in which the “immersants” of CREW dwell, however, are video-based, adding a completely different dimension to the experience, resulting in effects of profound ambiguity. Different channels of perception perpetually interfere, simultaneously causing a peculiar mixture of fact and fiction.

Notes

[1] See : http://www.crewonline.org/art/project/4.

[2] In «Performing phenomenology: negotiating presence in intermedial theatre», Kurt Vanhoutte and Nele Wynants set forth the post-phenomenological conditions for understanding this shift, whereas in «Instance: the Work of Eric Joris with CREW», both authors propose an anthropological approach formulated in terms of rite-de-passage and “liminality”.

Bibliographie

– Botvinick, Matthew et Jonathan Cohen, «Rubber Hands ‘Feel’ Touch that Eyes See», Nature, vol. 391, 1998, p. 756.

– Crew, en ligne,<http://www.crewonline.org/art/project/4>.

– Grau, Oliver, Virtual Art: From Illusion to Immersion, trad. Gloria Custance, MIT Press, Cambridge, 2003.

– Vanhoutte, Kurt et Nele Wynants, «Instance: the Work of Eric Joris with CREW», dans Bay-Cheng, Sarah, Chiel Kattenbelt, Andy Lavender et al., Mapping Intermediality in Theater and Performance, Amsterdam University Press, Amsterdam, 2010, p. 69-75.

– Vanhoutte, Kurt et Nele Wynants, «Performing Phenomenology: Negotiating Presence in Intermedial Theatre», Foundations of Science, vol. 16, no 2, 2011, p. 275-284.

– Nelson, Robin, Kurt Vanhoutte, Bruce Barton, et al., «Node: Modes of Experience», dans Bay-Cheng, Sarah, Chiel Kattenbelt, Andy Lavender et al., Mapping Intermediality in Theater and Performance, Amsterdam University Press, Amsterdam, 2010, p. 45-48.