Other Graphics

Mexican artists increasingly began to investigate alternative uses of photo copiers, fax machines, video cameras and computers since the late 1960s. These media captured the attention of art students and established artists as they entered into their daily life. At the same time, new media brought new problems and posed fundamental questions that were at the core of art history, for example: questions in relation to the aura, the art object as original and finished product, and the artist as genius creator. While the number of experiments increased the next decade, the mainstream art world took at least two decades to reflect on these practices and their impact on the history of art and culture at large1. To begin with, the troubled relationship between technologies and war complicated matters, while the mass consumption of media and the development of more user-friendly systems easily eliminated the sense of distinction as formulated by Pierre Bourdieu2.

The first experiments with copying machines began in the sixties, while the real take-over was the next decade. Artists like José de Santiago and Humberto Jardón used copying machines as a means for the production and reproduction of images. Copyart or Xerox art then emerged as buzzwords among artists who were using copying machines, such as: Santiago Rebolledo, Rubén Valencia, Maris Bustamante, Magali Lara, Yani Pecanins, Zalathiel Vargas, and Marcos Gabriel Macotela Kurtycz. But the cheap cost and popularity of copying devices caused skepticism among critics and exhibition organizers, for as artist Jardón recounts on the exhibition catalogue Other Graphics (1993): “in the eyes of the general public, copy art belongs to that sub-genre of artistic curiosities that emerged in the sixties and developed in the seventies; a sub-genre that nobody takes seriously; as a result of the daily contact with the copying machine they give it for granted3.”

On the other hand, not all traces of media art are electronic. In fact, independent and experimental films produced in Mexico from 1930s onward, already demonstrated a formal interest and “reflection on the medium itself” that reformulated the traditional production, exhibition, and thus perception of moving images4. At the same time, the release on the market of 16mm film, and later 8mm and Super8 films, triggered a boom in experimentation as the cost of film production lower considerably. The political and cultural implications of such devices were crucial, as media art pioneer Andrea Di Castro explains, “before the commercialization of portable video devices—both industrial and home devices—there were not vocabularies to oppose television. Television dictated the absolute value, the guideline of how images should be shown on the small screen, and how and for what purposes the equipment should be used. It is with the release on the market of the home videotape recorder, and more recently with high-resolution micro formats that images produced with video cameras provide the viewer with an alternative way of seeing the world5.” Independent films proliferated in Mexico, especially in the 1970s when groups of young film makers—the so-called “Super 8 film buffs” (Superocheros)—sprang up around utopian ideals of the power of these small formats to transform Mexican cinema6. However, the cost of film remained prohibitive from some, so filmmakers such as Rafael Corkidi, Katia Mandoki, Gregorio Rocha and Sarah Minter turned to video.

Video Traces

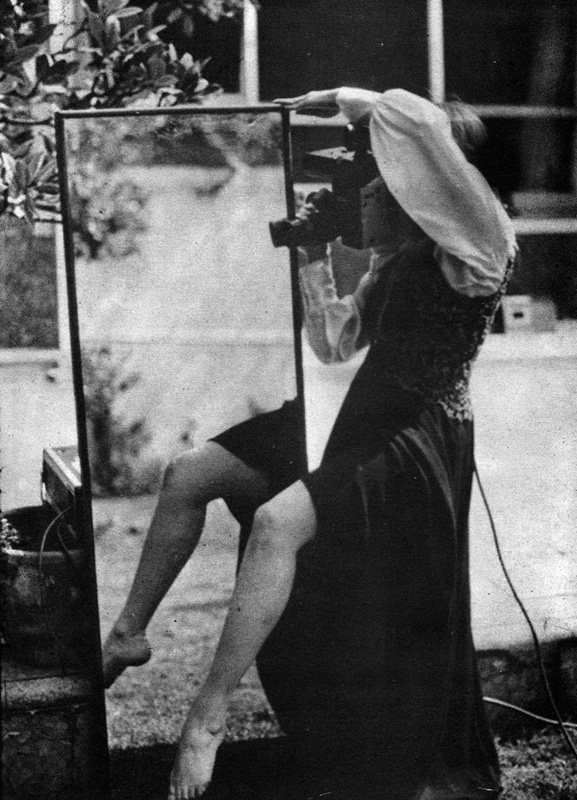

Mexico’s video-art pioneer Pola Weiss, first used a video camera as an undergraduate student in journalism at the Department of Social and Political Sciences at the National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM) from 1971 to 1975. As a student and later instructor, she wrote scripts and directed documentaries and TV programs; but she eventually shifted her attention from content to form and media, investigating alternatives uses of the video camera and the video signal itself. Although she initially defined her practice in relation to the media she knew best, television, the scope of her experimentation was clear as she named her firm ArTV in 1972.7 Convinced of television’s potential as artistic medium, she crated a set of works where she established an embodied relationship with the camera. With her hands on the camera, Weiss’s moving images comprised her own movement, hence, rather than her being the subject of the observer’s gaze, she fractured this relationship altogether, blurring the boundaries between artist, performer, image production and the world beyond. Her work focused on themes such as gender, identity, the body, and the urban context, and she also interrogated gender roles.8 Unlike her male-contemporaries, Weiss established a relationship with the camera which complicates the representation and reading of her body.

In 1976, Weiss traveled to New York, where she encountered works by Nam June Paik and other video artists for the first time. Thrilled to know that artists were experimenting with video in other countries, Weiss returned to Mexico City to produce a set of events and exhibitions aimed at disseminating video as an art form. In that context, the 9th International Festival of Video Art was held at the Carrillo Gil Museum in 1977, showing the work of Miguel Ehrenberg, Allan Kaprow, Shigeko Kubota, Les Levine, and Name June Paik, while Weiss represented Mexico with her video Cosmic Flower (Flor Cósmica, 1977).9 Despite Weiss’s enthusiasm to exhibit the work of international video art pioneers in Mexico, criticism was harsh, and as Weiss’s apprentice Alberto Roblest recounts, the exhibition provoked a kind of shock among the art community. “Obviously, video art is shown with 10 years of delay in Mexico. But her [Weiss], she is the first one who takes the risk and exhibits these videos in front of art and film critics, poets, writers, and artists. Obviously many contemporary critics discredited this art, others argued that they did not know this media and therefore could not comment on it, while some critics even said that only consisted in the manipulation of devices.”10 This skepticism toward video art continued throughout the 1970s and 1980s. Although Weiss’s production was continuous, her public events in Mexico fluctuated in relation to the agenda of Mexican art institutions, which ignored her work. Instead, she traveled abroad and participated at international festivals such as the Caracas Video Festival and the International Art Exhibition in Kansas, both in 1979, and the Athens Video Festival in Ohio in 1980. Weiss also exhibited eight of her videos at the Pompidou Center in Paris in 1979, and featured Videodanza Viva Videodanza (Video dance Life Video dance) in the 1984 Venice Biennial.11

Weiss shared with her contemporaries an autobiographical and experimental approach to video art, and while she experimented with chroma-key and solarization effects like Paik and Vostell had, it is considered that “one of her major contributions was the concept of ‘video dance,’ dancing actions performed for the camera. The dominant note in her work, nonetheless, was a search for identity, whether in terms of her origins, her body, or her feelings…”.12 This is especially true in works like My Heart, from 1986, in which close-up images of the artist’s body blend with footage she recorded of the aftermath of the 1985 Mexico City earthquake, which killed approximately 10,000 people. In this video, Weiss turns the divisions between the private and the public upside down, creating works that, despite the psychedelic aesthetics are profoundly personal. Additionally, as Jesee Lerner and Rita Gonzalez write: by “incorporating performance into a new form of expression that she labelled ‘videodanza,’ Weiss mixed movement research and layering of images into the body of her work. Her work has that sense of embodiment and free-form exploration akin to early feminist art (e.g. Carolee Schneemann’s eroticized body in performance and film, Judy Chicago’s deconstructed female in ‘The Dinner Party’ installation).”13

While teaching at the Department of Social and Political Sciences at the UNAM, Weiss pushed her students beyond the limits of television, thus engaging some of the new video artists. For example, Alberto Roblest and Cesar Lizarraga, two of her students formed the collective group “Two-Video” in 1988, and they produced numerous single channel video and video installations in the 1990s. In Roblest’s own words, Weiss’s teaching was far from traditional: “Her first class was like therapy, students talked about their problems and what we thought of life and other issues… She introduced us to collage, photography, yoga, and the basics of animation. With Pola we danced with the camera, she hated tripods, she made us sleep and dream along the video camera. For many students this was freaky, imagine for undergraduate students of public administration or political science!… Pola disliked those students who wanted to do television or ‘small theater’ with video… She never showed her own videos in class, only if students ask privately; [she shared her work] with students she considered different. She took us to her father’s home at the end of the second term, where she showed us for the first time her videos; then, a woman was there and I later learned that she was Paik’s wife, artist Shigeko Kubota.”14

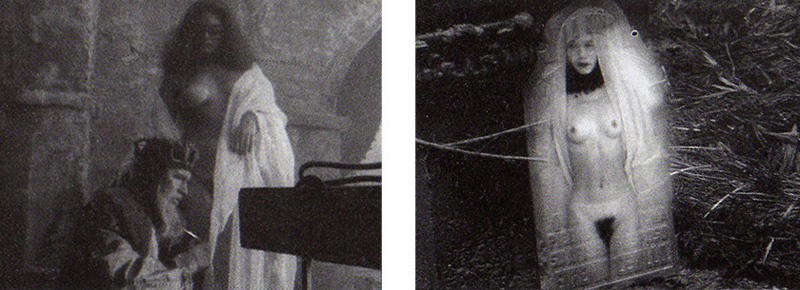

Filmmaker Rafael Corkidi, on the other hand, is not only one of Mexico’s pioneers of video art, one of its most enthusiastic supporters, and mentor of younger generations, but also one of the first media archaeologists. From the 1950s to 1970s he worked as film director and photographer on independent and private productions, among them Alejandro Jodorowsky’s Fando y Lis (1967) and El Topo (1969). Video, however, offered the autonomy that Corkidi had not found in film. As he puts it: “I always wanted a career that would allow me to express myself, the time came when I was unable to do so as a photographer, I needed to do more, it was then that I undertook the project Angels and Cherubs, which led me to realize that I had nothing more to say as photographer.”15 As a video artist, however, his work had just begun. In 1983 Corkidi released his first work entitled Figures of Passion (Figuras de la Pasión), in which he was able to be part of the whole process—from scriptwriting, production, photography, and postproduction to distribution. In the following years, he continued investigating local folklore, religious and mystical themes with a “leftist indigenista aesthetics.”16

In addition, Corkidi was also concerned with the construction of memory of video art in Mexico. He followed the pioneers’ traces, passing on their legacy to younger generations as cultural promoter and professor in four different cities in Mexico. In 1986, he organized the First Videofilm Festival in Mexico and the First Video Biennial in 1990; in the latter he included a historical selection of works, entitled Pioneers (Forjadores), by Francis García, Carlos Mendoza, Sarah Minter, José Manuel Pintado, Gregorio Rocha and Pola Weiss. Corkidi’s unconventional design for the historical section of the Biennial demonstrates his interest in the personal narratives of the artists: the installation consisted of a large monitor surrounded by four medium-size monitors. The central monitor displayed the interviews he conducted with the artists, while their works were played on the other four monitors.17 On the other hand, given Mexico’s centralist politics, the fact that Corkidi lived in Guadalajara, Puebla and eventually Veracruz, has been crucial in the formation of some of the established video and film makers in the country of the last two decades. In Guadalajara, for instance, Corkidi’s teaching had such an impact that “it was in this city where the video avant-garde established itself most of that decade. He was president of the jury for Vidarte 99, the most important video festival at the present, and he recently founded a school of video for young people and children in Veracruz.”18

Originally trained as an engineer, Andrea Di Castro worked with photography, video and installation, and in 1984 he began working with computers. He also played a key role in the legitimization of media art in Mexico, as an artist; founder of Mexico’s Multimedia Center, which he also directed from 1994 to 2001; professor at the National School of Painting, Sculpture and Engraving, known as “La Esmeralda”; as well as juror for competitions and mentor of younger media artists. In 1978, a group of artists including Cecilio Baltazar, Humberto Jardón, Sandra Llanos, Humberto Saldaña, and Di Castro presented at the Casa del Lago Intervalo Ritual: three happenings and installations, a collective creation with video, lasers and live music. A year after, the Casa del Lago exhibited Di Castro’s installation Videoevento, Cuerpo Idea, where he realizes that the experiments that he and his contemporaries were doing needed an cultural institution to show their work in order to reach the kind of public that could be interested in the intersection of art and technology.19 Among his single-channel videos are: The Other Face of Muybridge (1983), created in collaboration with Cecilio Balthazar; Video Portraits (1988); and Pasos por la Ciudad (1990). The Other Face of Muybridge is a visual study of the body that looks at the experiments by Eadweard J. Muybridge, updating them to explore the spatial and temporal possibilities of video.

Since the late 1960s, Mexican artists increasingly began to experiment with electronic technologies, making traces that have faded in and out over the years, and have left a fertile terrain for historical and critical inquiry. Mapping these histories—whether under the theoretical framework of media archaeologies as elaborated by Erkki Huhtamo or Siegfried Zielinski, or following other navigational principles and methodologies—remains a collective project. In such an effort, this paper discusses the pioneering work of artists living in Mexico City, as they made their way into a mainstream art world which was originally reluctant to investigate the ontology of the experiences produced in the evolving relationship between artists and new media. For reasons of space and time, I have only focused on a limited number of artists working from the 1960s to 1980s and have sketched a rough, if subjective, map with more gaps than absolute truths.

On the other hand, Pola Weiss continued producing videos in the 1980s, producing works such as Exoego and The Eclipse, which were presented along other videos by Weiss at the Museum of Modern Art’s exhibition “Polarizing” in 1982. The reception of her work at that time was more positive than in the previous decade, because there was an intention to reflect of the use of new media as valid medium of art within the art institutions themselves. In the exhibition brochure for Weiss’s “Polarizing” it is written: “Pola Weiss’s work is embedded in the contemporary trends of artistic experimentation; she constantly investigates new forms of expression and the crisscross of creative activities related to mass media. Her research is posed in relation to her need to bring artistic experimentation to all levels of everyday life. Video is thus legitimately a new medium of expression in the visual arts.”20

Through the 1980s and 1990s artists like Pablo Gaytán, Silvia Gruner, Alejandra Islas, Sarah Minter, Gregory Rocha, to name but a few, marked a new period of video production in Mexico. While Gruner’s work was more influenced by conceptual art, the rest focused on “urban subcultural scenes, indigenous struggles for basic human rights and land, and experimental narratives.”21

Electronic Systems

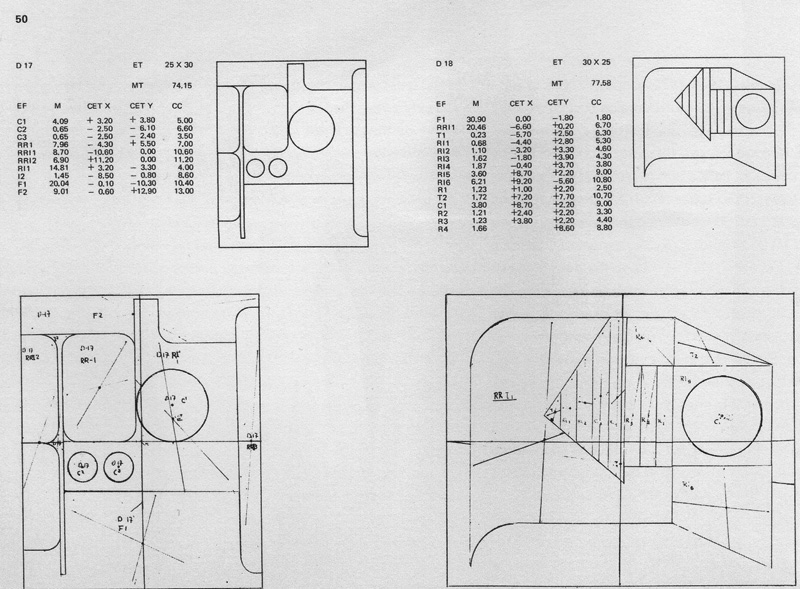

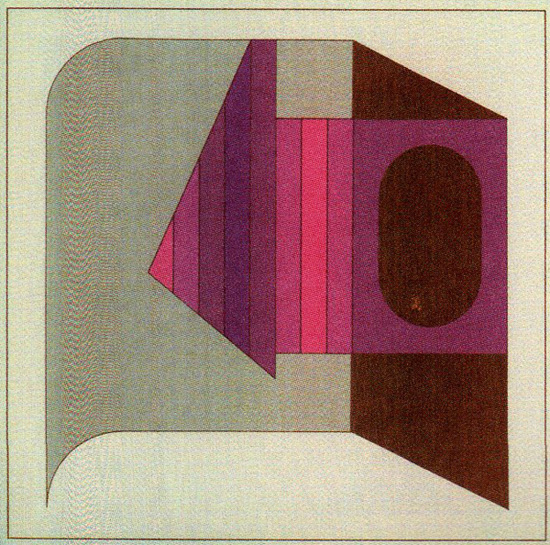

Abstract painter Manuel Felguérez is the first artist who worked with a computer in Mexico. While teaching at the San Carlos Academy, he reflected on the possibilities of the computer as a tool for artistic creation, able to effect “a transformation of the ‘system of syntactic rules’ into an aesthetic practice.”22 In 1972, Felguérez started this project by using one of the first computers in the country which belonged to the National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM). Since the time he had to work on the computer was very limited, he was granted a Guggenheim Fellowship and continued his project at Harvard University. There, he developed “The Aesthetic Machine,” a project that consisted in inputting information for the most representative compositional elements of his work into the computer, which produced a synthesis of the components to generate drawings that the artist used as a basis for developing a traditional painting or sculpture. According to Mexican art critic Cuauhtémoc Medina: “[t]his search for directly operating at the level of ‘structure’ or ‘syntax’ in his pictorial language was tantamount to transferring personal authorship to an external mechanism: a logical and automatic artist.”23 Felguérez’s aim was to “find out the number of variations that could be drawn from my drawings, that is, I wanted to know what kind of works I could paint the rest of my life. After a long research process, drawings finally began to be printed with a plotter, every eleven seconds!”24 However, Felguérez’s initial fascination soon faded away, and in fact he has not incorporated computers to his artistic practice since. Though he learned in the process that the computer was learning and somehow it was more sensible to his work, he “missed the workshop, my pigments, getting dirty, so I began to paint what I wanted, I put aside the drawings and never touched a computer again. »25 Although Felguérez did not continue his use of computers, his work is an important antecedent to media art history in Mexico. As Medina writes, Felguérez’s series “did not aim to go beyond subjectivity, but—on the contrary—to increase productivity by means of automation. In other words, this was a means of proclaiming and objectifying some kind of modernized subjectivity.”26

Mexican artists also used Fax machines, a medium that posed a whole set of possibilities and questions, as it enabled image production, but it also represented a means of dissemination and communication. The firsts works of what was later called Artefax were presented in 1989 at La Esmeralda as part of the exhibit Electrosensibility. The opening day, twelve artists from Mexico City; Baltimore, U.S.; and Copenhagen, Denmark were part of this event. The same year, another exhibition was organized, this time at the Metropolitan Autonomous University (UAM) Gallery; titled Compudiarte 89,it included works by the students of the university’s Arts and Design programs.27

Photography & New Media

While some artists experimented with electronic media and sought to validate their practices in museums and galleries, photography underwent its own restructuring. On the one hand, photographers sought to legitimize their practice within the field of art, while on the other, a group of photographers interrogated the entanglement between photography and reality in the legacy of Manuel Alvarez Bravo—who basically represented the only reference of photography in Mexico. These tensions were brought to the forefront in the 1978 and 1981 Latin American Colloquia, where the need to rethink the photographic tradition in light of technological developments played a key role.28 In the history of art in Mexico, photography’s artistic validation began with the first exhibitions at the Museum of Modern Art (Photography as Photography in 1984, and Memory of Time in 1989); the foundation of photography schools like the Active School of Photography; the formation of the Mexican Council of Photography in 1978; and the organization of five Biennials of Photography from 1980 to 1988, which led to the creation of Mexico’s Centro de la Imagen in 1993.29 In this context, the world of still images was transformed by what Manuel Castells calls the information-technology revolution, opening new alternatives to artistic investigations with still and moving images, and bringing further hybrid terrains where these divisions do not matter. As Alejandro Castellanos points out: “In the context of the celebrations of 1989, electronic technologies redefined the iconographic boundaries […] fully incorporating photography into the age of globalization and information technologies.”30

Knocking on Heaven’s Door

The intersection between art and technology was not acknowledged by cultural institutions and curators until the late 1990s. In fact, media artists themselves had to open the game by working at museums and cultural institutions in order to create spaces for the discussion and production of media art in the following decades. As a result of the growing experiments with new media in the 1980s, a set of exhibitions were organized during the half-decade from 1987 to 1992: in 1987 Fernando Camino presented his work at the Museum of Modern Art; the next year the Rufino Tamayo Museum showed three videos by Andrea Di Castro as part of the exhibition “Videocompugráfica”; in 1989 scholar and media-art supporter Javier Covarrubias organized “Compudiarte” at the the Metropolitan Gallery (UAM); and in 1992 the Museo de la Estampa exhibits Zalathiel Vargas’s “Cyber opera, electrographic sounds.”31 As the names of these exhibitions demonstrate, the use of technology functioned to distinguish the artistic experimentations with technology from more traditional art forms; thus key notions such as cybernetics and the entanglement between computers and art functioned to draw on the limits in contemporary art, thus creating tensions that until this day remain in Mexico and the rest of the world.32

It was not until the 1990s that cultural institutions in Mexico recognized artistic practices with electronic media as valid; when the National Councils turned their attention to the growing experimentation with new media, the first institutions dedicated specifically to the production, dissemination, exhibition and research of art and new media were created. Starting with the Multimedia Center (CMM), which was founded in 1994. The CCM’s mission has always been to encourage the use of electronic media in artistic production, which it does by offering a non-academically affiliated, educational programme, as well as a set of activities that seek to provide access to the latest technologies for artists of all disciplines, such as dance, video, and audio. Located at the National Arts Center, the CMM has its own gallery, named after computer pioneer Manuel Felguérez. It is also a space for critical and historical reflection on the use of new technologies in art and its implications in various aspects of society. Founded by Andrea Di Castro and Javier Covarrubias, since 1994 the CMM has gone through different administrations and changes. However, the majority of artists who have shaped media art practices from the 1990s onward have trained at there, in the departments of Audio, Interactive Systems, Moving Images, Robotics, Virtual Reality and Research. Among them are Tania Aedo, Arcángel Constantini, Adriana Calatayud, Fernando Llanos, and Gerardo Suter.33 The CMM’s foundation thus represents one of the greatest achievements in the field of media art.

Following the foundation of the Multimedia Center, other spaces and events were created, demonstrating the growing importance of media art in Mexico and the need to rethink these practices in relation to contemporary art and art history. In 1998 The MUCA Museum (University Museum of Arts and Sciences,) opened its Black Box, a space devoted to electronic art.34 The previously mentioned Centro de la Imagen also opened a space devoted to the dissemination of video art, the Sala del Deseo (“Desire Room”), and later created a media art space with the purpose of providing technical and also conceptual support for photographers who wanted to use digital media named the Sala del Cielo (“Sky Room”). In fact, the Sala del Deseo is the result of the initiative and work of artists linked to La Esmeralda art school, among them Sarah Minter and Gregorio Rocha, who programmed a series of video screenings and events with a grant they received from the National Council for the Arts, thus turning a small space of the Centro de la Imagen into a room for the moving image.35 In 2001, the Rufino Tamayo Museum created Cyberlounge, a space within the museum devoted to exhibit net-art, sound-art and video-art projects. That same year the National Council of the Arts created the Special Projects Unit, (UPX) in order to work as a ‘laboratory of video’ in recognition of this medium as an artistic tool.” However, due to a corruption scandal related to the director of the UPX, Dolores Creel—sister of interior secretary Santiago Creel during Vicente Fox’s administration—the UPX closed in 2004.

The creation of Laboratorio Arte Alameda (LAA) in 2000 is also a major accomplishment in the history of media art. Conceived as a laboratory for experimentation and electronic art production, : “the LAA’s profile was defined in relation to the existing gaps between the institutions devoted to contemporary art. Hence, the LAA emerged as a space dedicated to the research, production and promotion of electronic art. The LAA’s programme includes exhibitions, experimental film and video, performances and concerts, workshops, lectures, guided tours and an electronic publication. The LAA is distinguished by its fostering of artistic production through the development of works created specifically for this space.”36 In the last several years, the LAA’s mission was been reshaped in relation to the construction of historical revisions of media art; as part of the institution’s ambitious project (Ready)Media: Towards an Archaeology of Media and Invention in Mexico (2009-2010) they invited “a group of curators, researchers and artists to make a critical reading of the archive gathered during the first ten years of Laboratorio Arte Alameda. This reading was made not only with a retrospective gaze in mind, but with the idea of proposing new documents to include in the archive. The result is an audiovisual series with more than 23 hours and the participation of more than 200 works, divided into seven programs.”37 Finally, since 2010 the Príamo Lozada Documentation Center —named in memory of LAA’s founding curator—has been open to the public.

On blank Spaces and Closing Remarks

The traces sketched above could be expanded with data provided in a hypertext-like manner, including a long list of names and events that have been omitted in this short paper. In fact, the discussion was left at a point where the number of artists using new media increased to such an extent that data is no longer manageable. However, I recognize that no history fits within a text, nor an author’s collection of texts, nor even within a complete archive. With this in mind, I would only add that the popularization of new technologies, the inclusion of media arts into the curricula of Mexico’s art schools, as well as the organization of art festivals in different states of the country throughout the 1990s and 2000s have driven the evolution of media arts in Mexico. As in many contemporary societies, Mexico has reached the point that some imagined, but did not expect to see in such a short length of time: if the virtual reality imagined by early enthusiasts like Jaron Lanier has not yet come to being, its augmented version nearly defines today’s media cultures.31

Notes

[1] This paper draws from my thesis entitled “Electronic Art in Mexico” (Mexico: Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana, 2002) and my continuos work on the history of media arts with particular focus on Mexico and more recently Latin America. See: http://heartelectronico.org

[2] According to Bourdieu art objects are the objectification of a relationship of distinction, for their production and ownership suppose a set of dispositions that are not equally distributed. Pierre Bourdieu, La distinction : critique sociale du jugement (Paris, Éditions de Minuit, 1979).

[3] Humberto Jardón, “Ser apéndices de la máquina,” Otras Gráficas (México: Academia de San Carlos, 1993) 117. My translation.

[4] Sarah Minter, “A vuelo de pájaro, el vídeo en México: sus inicios y su contexto,” Vídeo en Latinoamérica, Una historia crítica, ed. Laura Baigorri (Madrid: Brumaria, 2008) 159. My translation.

[5] Andrea Di Castro, “Notas sobre el desarrollo del Video,” Otras Gráficas (México: Academia de San Carlos, 1993) 59. My translation.

[6] Álvaro Vázquez Mantecón, “Ideology and Counterculture at the Dawn of Mexican Super 8 Cinema,” La era de la discrepancia: arte y cultura visual en Mexico 1968-1997, ed. Olivier Debroise (Mexico: Turner/UNAM, 2007) 62-65.

[7] While historical accounts of the history of video art and vide are scarce, Pola Weiss’s work is well documented in the book by Dante Hernández Miranda, Polla Weiss, Pionera del videoarte en México (México, Comunidad Morelos 2000). Most of the information related to her work in this text comes from this source.

[8] Fragments of numerous works by Weiss can be streamed on-line at the Netherlands Media Art Institute website

[9] The Festival was organized by Jorge Clusberg, the Argentine art critic and curator who played a key role in the production, dissemination and criticism of international avant-garde styles in Argentina and Latin America. Sarah Minter, Op. Cit., 161.

[10] Interview with Alberto Roblest by Dante Hernández Miranda. September 25, 1996. Quoted in Dante Hernández, Op. Cit.,19. My translation.

[11] Despite the lack of public funding for artists at the time, Weiss managed to exhibit her work internationally. Among her solo shows are: “Visual Arts and Video with Pola Weiss,” held at the Akademie voor Beeldende Kunst, Sint Joost, Breda, and at the Akademie vooe Beeldende Kunst AKI Enschede in Holland in 1981; and “Pola Weiss” at the Monte Video Art Gallery, Amsterdam, Holland. She was also a juror at the 4th International Festival of Cinema, TV and Video of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil in 1987. Dante Hernández Miranda, Op. Cit., 36. Also see Pola Weiss’ online archive.

[12] “Pola Weiss,” La era de la discrepancia: arte y cultura visual en Mexico 1968-1997, ed. Olivier Debroise (Mexico: Turner/UNAM, 2007) 302.

[13] Rita Gonzalez and Jesse Lerner, “Video”, Mexperimental Cinema: 60 Years of Avant-Garde Media Arts from Mexico (Santa Monica, CA : Smart Art Press, 1998).

[14] Alberto Roblest, interviewed by Sarah Minter. Quoted in Sarah Minter, “A vuelo de pájaro, el vídeo en México: sus inicios y su contexto,” Vídeo en Latinoamérica, Una historia crítica, ed. Laura Baigorri (Madrid: Brumaria, 2008) 161. My translation.

[15] Rafael Corkidi, Quoted in “Homenaje a Rafael Corkidi, [Trans]piración poética,” Transitio MX 01 (México: CONACULTA-INBA, 2005) 179.

[16] Rita Gonzalez and Jesse Lerner, “Interlude”, Mexperimental Cinema.

[17] Hernández, Pola Weiss, 109-110.

[18] Transitio MX_01, “Homenaje a Rafael Corkidi, [Trans]piración poética,” Op. Cit., 181.

[19] Andrea Di Castro, “Notas sobre el desarrollo del Video,” Otras Gráficas (México: Academia de San Carlos, 1993) 59. My translation.

[20] Museo de Arte Moderno, “Solarizando,” Quoted in Dante Hernández, Op. Cit., 49-50. My translation.

[21] Rita Gonzalez and Jesse Lerner, “Video,” Mexperimental Cinema: 60 Years of Avant-Garde Media Arts from Mexico (Santa Monica, CA : Smart Art Press, 1998).

[22] Manuel Felguérez, quoted in Cuauhtémoc Medina, “Systems (Beyond So Called “Mexican Geometrism),” La era de la discrepancia, 131.

[23] Medina, “Systems,” La era de la discrepancia, 131

[24] Masha Zepeda, “Manuel Felguérez, pintor visionario,” Interview with Manuel Felguérez. By Masha Zepeda, Tierra Adentro 114, February-March (Mexico: CONACULTA, 2002) 33. My translation.

[25] Loc. Cit.

[26] Medina, “Systems,” La era de la discrepancia, 131. In 2002 The Multimedia Center organized a historical exhibition of Felguérez’s work at the National Arts Center. “Preview, una revisión histórica. La Máquina Estética,” was curated by Edgardo Ganado Kim and it ran from September 26 to December 8 2002. See: Carlos Paul, “Develan mural escultórico de Felguérez creado para celebrar 50 años del Auditorio Nacional,” La Jornad.

[27] Mauricio Guerrero, “Arte Fax: un reporte en Encuentro Otras Gráficas,” Otras Gráficas (Mexico: Academia de San Carlos, 1993) 102.

[28] César Vera, quoted in Alejandro Castellanos, “Pasajeros en tránsito,” Tierra Adentro 105 August-September (Mexico: CONACULTA, 2000) 7.

[29] From 1993 on, the Centro de la Imagen has devoted to the documentation, exhibition and research of photography and image production in Mexico. See: centrodelaimagen.conaculta.gob.mx

[30] Alejandro Castellanos, “Pasajeros en tránsito,” Tierra Adentro, 4. My translation.

[31] Adriana Malvido, Por la Vereda Digital (México: CONACULTA, 1999) 159.

[32] For a discussion of the tensions between contemporary art and media art, see Claire Bishop’s controversial “Digital Divide: Contemporary Art and New Media,” Art Forum (Sept 2012) 434-441.

[33] One of the first artist to teach a workshop at the Multimedia Center is photographer Pedro Meyer, considered a pioneer in combining photography and audio on CD-ROM.

See: http://www.pedromeyer.com/galleries/i-photograph/acota.html. For an in-depth discussion of the Multimedia Center’s history see Humberto Jardón, “Cut/Copy/Paste. Contextualizando el Centro Multimedia a quince años de su fundación”, available in Spanish here.

[34] Media curator Elías Levín was the founding curator. He also coordinated the Video department at Museo Carrillo Gil and numerous media exhibits and festivals. For many years he had a column in Mexico’s news paper Milenio Diario specifically devoted to electronic art.

[35] I have devoted a paper to the history of both Sala del Cielo and Sala del Deseo in Erandy Vergara, “Entre el cielo y el deseo: fragmentos de una historia de las imágenes técnicas,” Luna Córnea 33: Viajes al Centro de la Imagen (Mexico: Centro de la Imagen/CONACULTA, 2012) 385-395. An electronic version in Spanish can be downloaded at heartelectronico.

[36] Laboratorio de Arte Alameda Catalogue. September, 2001. My translation.

[37] (Ready)Media: Towards an Archaeology of Media and Invention in Mexico. Edited by Laboratorio Arte Alameda. See: www.artealameda.bellasartes.gob.mx

[38] This lengthy quote by Ryan clearly outlines the early dreams of virtual reality that I refer to: “a computer-generated three-dimensional landscape in which we would experience an expansion of our physical and sensory powers; leave our bodies and see ourselves from the outside; adopt new identities; apprehend immaterial objects through many senses including touch; become able to modify the environment through either verbal commands of physical gestures; and see creative thoughts instantly realized without going through the process of having the physically materialized.” See Marie-Laure Ryan, Narrative as Virtual Reality (Baltimore, Md.: London: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2001) 25-47.