At the core of my oeuvre and of my artistic practice is the fact that you are not allowed to murder actors. They are a protected species. While they are brilliant at pretending to die – which they do with great aplomb night after night – they never actually do. Theater is a medium that represents society: a mirror. Actors represent death. The theater building with all its technical apparatus supports the lie; it enables the creation of magic. I like to see the theater as a dream machine.

On the other hand, an object chiefly represents itself. It simply is. The artist makes every attempt to allow the object to be an autonomous artwork. Perhaps even timeless. It is certainly a product of the period in which it is made, but it can easily be abstract – pure form. The museum, the white cube, displays the object as nakedly as possible. As honestly as possible.

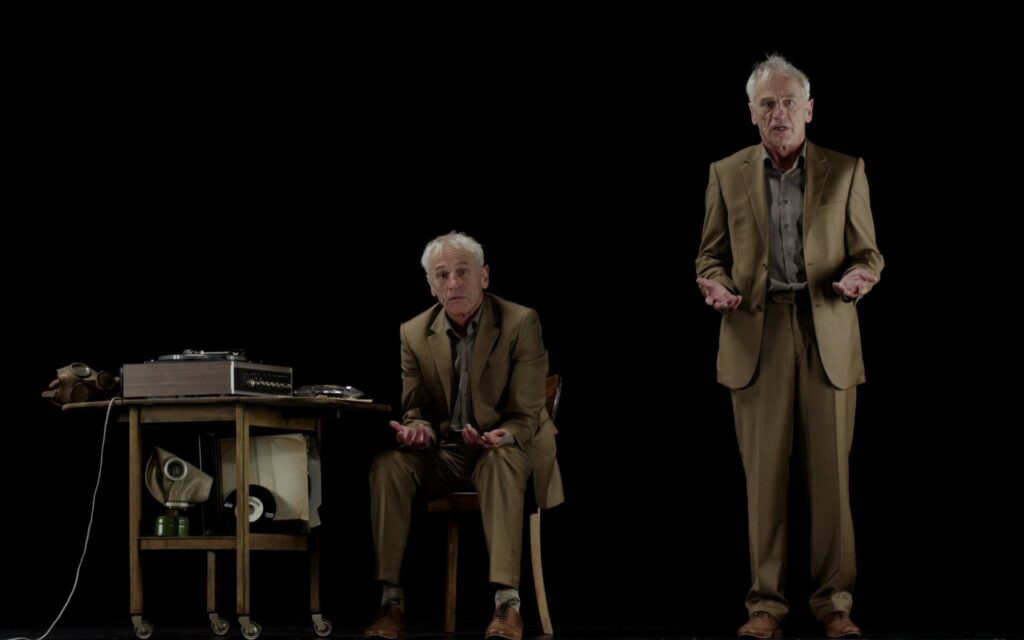

In my work, Objects (dead matter) and Subject (people, living matter) are constantly intertwined. Objects are often infused with “performative characteristics,” while humans have “objective” characteristics. Objects carry out dramatic actions, and actors are put on display in the museum.

When R2D2 “dies” in Star Wars, the audience is emotionally affected. We are upset when a machine breaks. “A machine dies” is an incredible sentence. Homo sapiens has a genuine, empathic relationship with his objects and machines. Our most intimate relationship was arguably the one we had with our teddy bear. We think something is missing in life if we accidentally leave our smartphone at home in the morning. The globalized world would be impossible without computers. Our daily life: sex, communication, information, production, all takes place via a screen. Most of us will spend around eight hours a day sitting in front of a screen.

Marianne Van Kerkhoven said that the most revolutionary invention for dance in the past century was the rubber dance mat. The dance mat has altered dancers’ entire arsenal of movements. Before it was invented, dancers always had to remain in an upright position, because it is impossible to slide across a wooden floor. The mat is what makes all the groundwork possible.

My performers are often physically linked to machines. I hope that the two representational models – theater and visual art – will influence one another. That the object will make it impossible for the performer to “lie.” That he or she will have to learn the language of objects, and therefore will have to be in the moment, with his theatrical problems and his actual physical problems. On the other hand, I also hope that the object will speak the language of the theater and will lie. The “lying object” is something highly contemporary; our computers can no longer be trusted; and our privacy is sold right from under our noses.

In what follows, I have made a selection of my works, focusing on the different forms that the performer–the actor in my work–can take: people, cyborgs, robots, machines and objects. When the differences between humans and things, between “subject” and “object,” disappear, then the boundaries between the museum and the theater also vanish. When things are no longer simply dead and humans are no longer simply alive, the white cube and the black box become interchangeable. The result may well be a Beckettian grey. My work is a series of designs, consequences of this way of thinking.

The first two works are from 2003 and are probably also the most important ones. The rest of the works are consequences of these two fundamental pieces.

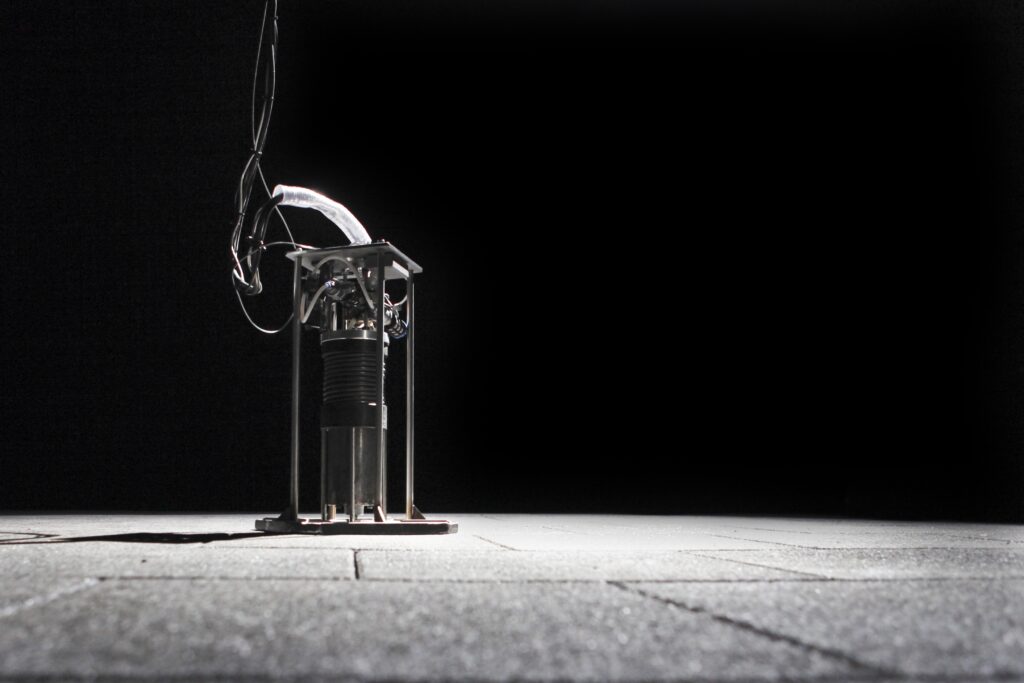

DANCER #1

A grinding disc with a steel “L” connected to it. Like a mini theater piece. A dramatic one-act play with a beginning, middle and end. Light off, light on, drama, light off, light on. Applause. The machine, the performer, is bought, used and thrown away.

IN

An actor in a sensory deprivation tank. The water is exactly 37°C. His five senses have all been disabled: smell, sight (by the lamp in front of him), hearing, touch and taste, which sends the performer into a trance. The actor is surrounded by his object; the machine forces him into a particular state of being. His breathing and heartbeat are amplified. IN is based on Samuel Beckett’s novel “Company.” But I also wanted to take a “still” from a performance. As if you can freeze a performance in a single frame, just like a film. All that theatrical tension frozen in a single moment.

HEART (2004)

A single performer stands on stage. The heartbeat is amplified and in real time. Every 500 heartbeats, she is pulled backwards. Eight metres further back, she slams into a mattress behind the curtain and falls from a height of 3 metres onto a mattress on stage, before returning to the initial position and waiting for the next action. Here too, a “system” or machine is central. The entire dramatic action is produced by the machine. The performer’s heartbeat is essential, and adrenaline makes the heartbeat and hence the mechanically sealed system go faster and faster, increasing the frequency of jumps.

ACTOR #1 (2010)

ACTOR #1 is based on Lessness by Samuel Beckett. Three installations show three variations on chaos and order. Matter (MASS), the mini-human or homunculus (HUMINID), and the machine (DANCER #3).

MASS

An open box: 4 x 4 metres, 1.10 m high. Inside, heavy smoke is sculpted by miniature ventilators controlled by Max / MSP. The audience stands around it. Here, the performer is pure matter.

HUMINID

A classic video projection on a doll. A simulacrum. Strangely enough, 50% of the audience believed that Johan Leysen – the projected actor – was literally there, even though he was only 45 cm tall.

DANCER #3

A small, jumping robot. The robot can sometimes execute his jumps, sometimes not. If he falls, he is pulled upright by another machine. The programming is largely random. I have no control over this.

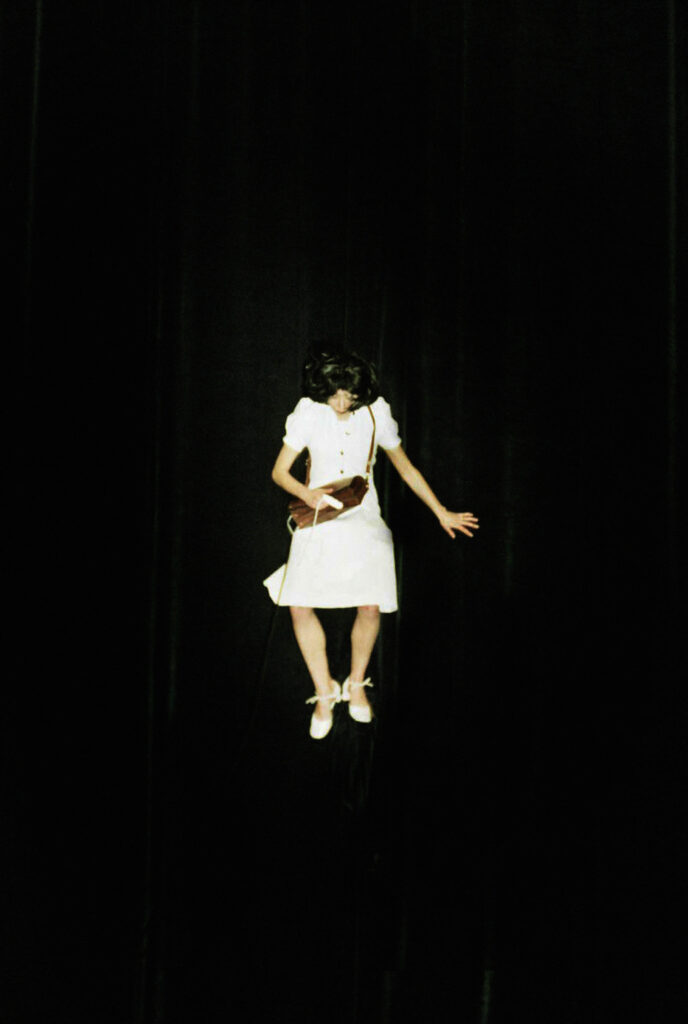

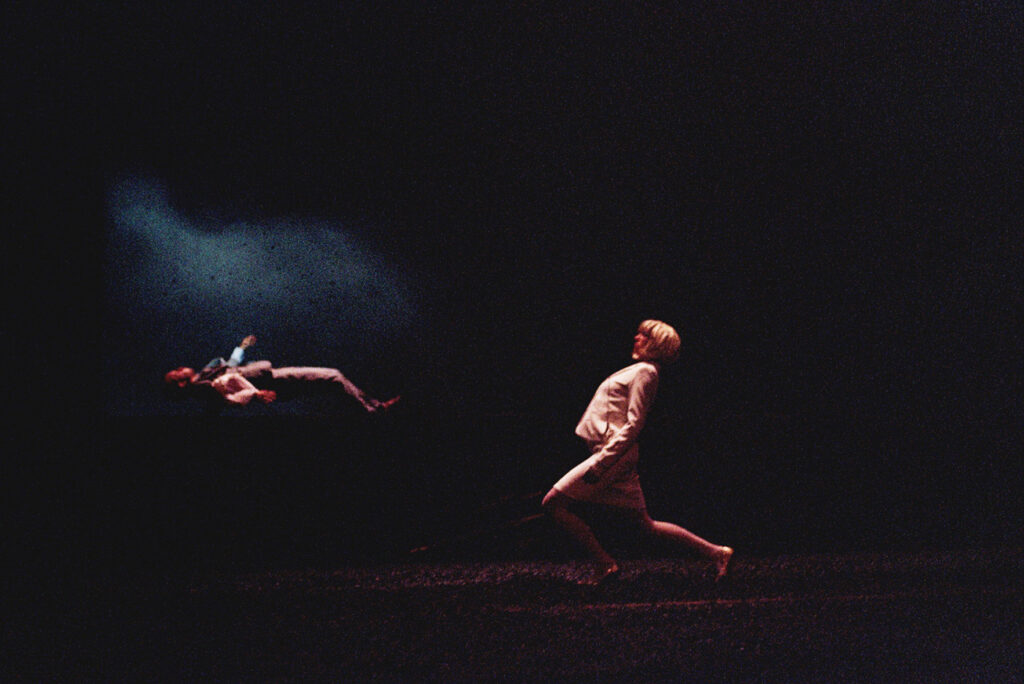

II/II/III/IIII (2007)

A dance piece: a solo, a duet, a trio and a quartet, each time the same choreography, and always 15 minutes long. Based on the “Pas de quatre” in Swan Lake. The machine, a giant mobile, is capable of lifting up the dancers and letting them float. The dancers try to remain perfectly synchronized; the machine inhibits this. The entire rehearsal process was about understanding the machine. And vice-versa: the technicians keep on technically altering the machine at the dancers’ request.

END (2008)

Ten figures, machines / people, move across the stage from right to left. The first figure, based on the Stachanovites, pulls the sky and the earth, which are projected onto the backdrop. He pulls on a cable, which is linked via Max / MSP to not only the image, but also the light, and the sound. He thus pulls forward the entire carousel. Each of the figures has a its own dramaturgy: one is based on a text by Alexander Kluge; another on the Stachanovites… The text is a sequence of events; horrors from the 20th century. Here, the performers all represent “figures” (a term which Nazi camp guards used to refer to their prisoners) – the living dead.

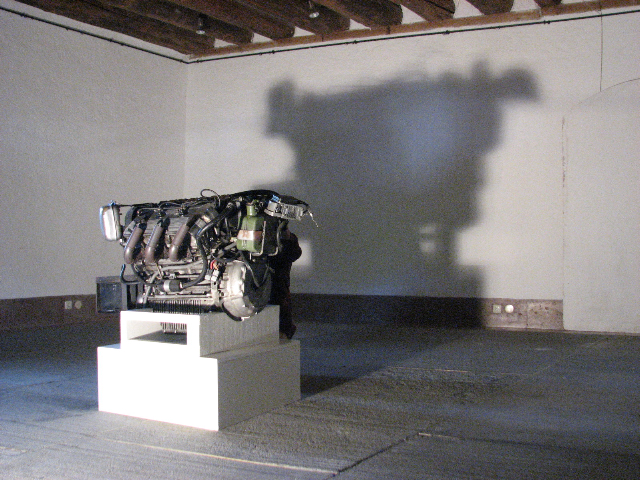

DANCER #2 (2009)

A real performance. A V6 engine that ignites automatically every half an hour, building up over a period of a few minutes to its full capacity, only to shut down again automatically. This is a true “performance,” 120 horsepower let loose in the space.

M, A REFLECTION (2012)

A solo for Johan Leysen with texts written by Heiner Müller. The mirror image, the twin, the other is a common thread running through Müller’s writing. This was a compilation of discussions between Müller and Alexander Kluge, and Müller’s prose works and poems, performed on stage by Johan Leysen and his virtual double. For this performance, we developed a technology that makes it impossible for the audience to distinguish between the real and the virtual actor.

DEAD BRASSBAND (2014)

A completely automated orchestra. Here we see one of the last areas that human beings are keeping for themselves – music – also being taken over by the machines. And sadly, these machines will pass the Turing test. The difference between the music played by the robots and that played by humans is barely distinguishable.

EXIT (2011)

This is a solo for Alix Eynaudi. Here, the performer has been given much more space. This is a performance in which movement, language, video, sound, temperature and light serve a single purpose: to get the audience to sleep. This results in the audience entering into a kind of in-between state: half dream, half reality. The theater as dream machine.

UNTITLED (2014)

UNTITLED is about the working poor, a topic close to my heart. In my oeuvre, I have made a single big shift. First, the performer is still physically linked to his object. Then the performer has disappeared: he has dissolved into the entertainment. Flesh, blood, sweat and shit have disappeared: “pure entertainment” is all that remains. The only real people left are sitting in the audience, and they are allowing themselves to be entertained.

EXOTE (2011)

I have ended up including a single visual art work, EXOTE. This garden consisted entirely of invasive species: plants, birds, fish, frogs, insects, crabs and a squirrel. These species do not occur “naturally” in Belgium. In principle, there is nothing wrong with these plants in themselves; it is primarily because of human intervention and pollution that they can be invasive and therefore damaging to indigenous plants. This is a negative Garden of Eden.

SHELL (2010)

Here, it is once again the object itself that undertakes a dramatic action: an outdoor firework in a display cabinet. A tamed beast.

Methodology

My working method is classic: 90 % of the works that I have produced started out with text. I read a text, and add a classic dramaturgy – previously in collaboration with Marianne Van Kerkhoven, and now with Kristof van Baarle. This dramaturgical analysis can sometimes take two years. During this analysis, the text itself often disappears. The contents of the texts determine the techniques that will be used. Of course, there are writers who are in close affinity with my world: Beckett, Kharms, Kafka and Müller.

The technology used should still serve a purpose, give shape to the contents of the analyzed text. Through this, the machines become an essential part of the performance or the installation. In the piece, performers and objects are treated as equals. They have to adjust to one another.

A technical defect will mean that the performance has to be cancelled.

Because the objects are treated as full-fledged performers, it often happens during creative periods that they themselves will communicate what they want to look like, or what they want to “perform.” For me personally, the greatest challenge is to recognize this during the rehearsal process.

During the production process for Dancer #3, the jumping robot, we noticed that the robot itself liked to jump in a certain way. He has a specific way of moving, and we acknowledged and amplified this. The further we advanced in this process, the more “lively” and thus “unheimlicher” the machine became.

In M, A REFLECTION, the projection “directed” the entire process. Johan had to adapt himself as an actor to what his virtual twin counterpart demanded from him.

Over the course of history, the relationship between man and machines has repeatedly been compared to his relationship with God.

Indeed, the essence of godliness is to have control over everything, to achieve omnipotence. The human, as an imperfect, unpredictable, uncontrollable and mortal being, longs for the domain of the perfect, the controllable and the immortal. The human longs for the mechanical; he wants to make the robot or be the robot in order to escape from his own imperfection and mortality.

My “figures” find themselves in the eye of the storm of this desire. They make the transition from human being to machine, and vice-versa. They are almost cyborgs. But the tragic thing about them is precisely this “almost.” They are in-between beings, in the midst of transition, and suffering from the fact that they are neither one thing nor the other. However, the result is not a big dramatic movement; all the drama is internalized. As a result, they often stand still, frozen on the spot like a broken machine, or one that endlessly repeats the same nodding movement.

The “muselmanner” or Agamben’s “figure” is perhaps the central figure in my work. The half- dead or half-living, half performer or half thing; there is no longer much evolution in this state of being. My figures are mostly the result of a system. Humans have created this system themselves (I am the one who creates it in the theater) and have then lost control.

And yet we cannot stop ourselves from carrying on. The half-living ask themselves how things could have come to this, and are left in despair. The half-dead are bogged down by indifference. When the human being or the performer takes up a smaller portion of space, space is opened up for something else.

Contemporary ecological and technological developments lead to a drastic change in human beings’ place on earth. I think that humans themselves specifically long to make themselves superfluous. The age-old idea of the homunculus, artificial life, has never been so close. In my work, I start from the idea that humans will disappear from the world. Heiner Müller said in an interview with Alexander Kluge: “But the thing that occupies that space can change continuously. This does not have to be a human being; it can also be a computer or a plant-based substance, whatever.” According to some philosophers, we now find ourselves in a kind of post-history of satiety, stagnation, resignation and the slow crawl towards extinction. Likewise, Benjamin’s “Angel of history” can only look on as the rubble piles up, while the end sucks him in. All humans seem to have the same apocalyptic urge.

So what would the world look like if humans were gone? This is a challenging mental exercise for Westerners. A single image or starting point illustrates the emptiness that will remain after our destruction: a robot that is sent out into the no-go zone after the nuclear disaster at Fukushima to pray for the victims.