In 1892, American dancer Loïe Fuller became one of the first performers to explore the potential of electric light, when she staged her Serpentine Dance at the Folies-Bergere in Paris1. Fuller’s experiments with fabric and coloured lights, at a time when theatres were just beginning to convert gas to electricity, stunned audiences and transformed her female body into what the London Standard, in 1900, called a “kaleidoscopic vision” (Merwin, 1998, p. 73-92). Fuller has since been championed as a feminist figure for her fusion of art and science and the way the spectacle of her stage show worked to defer fixed representation, in an “ontology of becoming2”. I read Fuller’s cyborg body in performance as an example of posthuman dance, which I trace also to the work of Canadian intermedia performance artist Freya Olafson. Olafson’s 2013 performance artwork HYPER_ features a combination of dance, computer animation and improvisations with technology that enact upon the dancer a visual experiment in body erasure. Both Fuller and Olafson employ imagery in their work that positions them between states of disembodiment and multiple embodiment. Likewise, both artists work with expressive materials, made “lively” by invisible corporeal labour; their female bodies disappear within moving swathes of fabric and projected images, yet it is precisely their bodies, which serve as both living canvases and energetic operators, that make such non-human performativity possible. In this way, I see gendered embodiment as crucial to a feminist-posthuman analysis of these intermedia dance performances. Fuller and Olafson dance more than a century apart yet their performances are driven by a similar ethos, one that demonstrates the persistent signification of the female body, even in its disappearance3.

Analyses of dance collaborations with technology often extol the potential of such works to highlight distributed agency and imagine new possibilities for embodiment and representation, or their ability to effectively convey the impact of technology on modern life4. Critiques of intermedia dance might object to the ways in which technological props and extensions can limit the range of expression for the human performer, but rarely are such works examined from the intersection of posthuman techno-embodiment and identity politics5. Human markers of identity such as gender or race are seldom taken into consideration in critical analyses of intermedia dance works. Both Loïe Fuller and Freya Olafson perform work that addresses the category of the “human” in their cultural present, yet even as they contribute to general definitions of existence, they use their specifically gendered bodies to do so. In employing the emergent technology of electric light, Fuller’s Serpentine Dance acted as a Symbolist response to the rapid changes of modernity in fin de siècle North America and stood as a prediction for future cinematic visions. Similarly, Olafson’s use of multiple screens and projected 3D footage comments directly on the ways in which subjectivity in the digital age has become increasingly layered and fragmented. Rather than view these performers as metaphors for the general human subject of their respective historical moments, however, Fuller and Olafson’s work benefits from an analysis that specifically focuses on the role of the female body (and its various stages of spectacle and embodiment) in their live dance productions. In analyzing Fuller and Olafson’s work both visually, in terms of an aesthetics of disembodiment and transformation, and formally, in terms of their facilitation of the displacement of dance movement from their own bodies to the expressive materials they manipulate, I wish to expose a historical continuum of the desire, not just for imagined alternate existences and possibilities for embodiment, but, more troublingly (in part because it is screened on the female body itself), the desire to see woman erased. I argue that Fuller and Olafson are commentators on, not casualties of, this social anxiety; these artists know that the sexualized female presence, itself, already illustrates a kind of objectification that troubles the human/non-human binary, and as such, this presence haunts their performances.

Cyborg Dancers

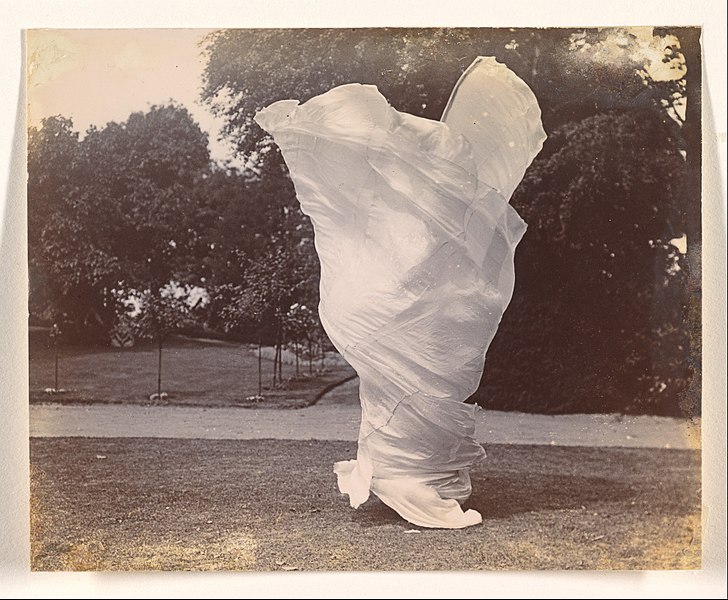

Loïe Fuller’s signature “Serpentine” and “Fire” dances involved a costume made of many yards of heavy white silk, manipulated invisibly from within by hooked bamboo canes, which were designed and patented by Fuller. Guiding the fabric in spirals and loops with her canes, Fuller orchestrated a fluid spectacle that appeared like a rippling sculpture.

She was also one of the first performers to harness the power of luminescent chemical salts for stage lighting, and Fuller’s magic lanterns, which shone on her from a variety of angles, were fitted with translucent, colourful gel lenses that projected the playful dance of colours onto her moving costume. She also devised and patented a glass floor, upon which she danced, lit from below. The aura of enchantment that Fuller’s performance bestowed upon her audiences is evident in Isadora Duncan’s description of the show:

“Before our very eyes she turned to many-coloured shining orchids, to a wavering, flowing sea-flower, and at length to a spiral-like lily, all the magic of Merlin, the sorcery of light, colour, flowing form…She transformed herself into a thousand colourful images before the eyes of her audience. Unbelievable. Not to be repeated or described6.”

Notably, Duncan compares Fuller not only to natural images but to the male sorcerer Merlin, of Arthurian legend, implying that the power of Fuller’s transformation is enhanced by her evasion of the female form via her appropriation of the masculine tools of magic and electricity. Indeed, Fuller’s love of science and her innovation in stage lighting were uncommon for women at the time. She was a member of the French Astronomical Society, was well-respected in the French scientific community, was close friends Marie Curie and had her own theatre in the Paris Exposition of 1900 (Gunning, 2003, p. 83). It was Fuller’s use of technologies of light, in particular, that contributed to the spectacle of her stage show as precursor to cinematic technologies. She was the first to use a “black-out” prior to the beginning of her stage performances, and in dancing within dozens of projected lights, she effectively turned herself into an animated screen, blending flesh and technology to produce what I see as a kind of cyborg body.

The figure of the cyborg is key to discourses of posthumanism. In her early work, Donna Haraway positioned the cyborg as a kind of “boundary rider”—a fluid figure somehow both intrinsically female and also capable of transcending oppressive categories of gender and race. The feminist potential of the cyborg is located in her gendered body, a machinic-organic hybrid that “skips the step of original unity” and acts as a figuration for something Haraway calls “worlding”: a convergence of forces (including the human) that come together to produce identities and relations (Haraway, 1991, p. 149). I see Fuller as a precursor to Haraway’s cyborg in that her performances staged an interface between technology and the body, evoking the feminist potential of the cyborg. Yet, feminist analyses of Fuller’s work often cite her transformative potential—the erasure of her fixed female form—as liberating, rather than view her hybrid dance as a kind of assemblage or “worlding.” Certainly, Fuller’s skirt dances can be read as a protest against the commodification of woman, but we must remember that the magic of her metamorphosis into a dehumanized spectacle in part hinges on the very thing it is erasing: Fuller’s own female body, which was fetishized on the many posters that advertised her stage show. These posters implied that Fuller might be dancing nude beneath her costume, when in reality the audience would experience a kind of reverse striptease, in which her body became increasingly abstract and dehumanized.

Posthuman Striptease

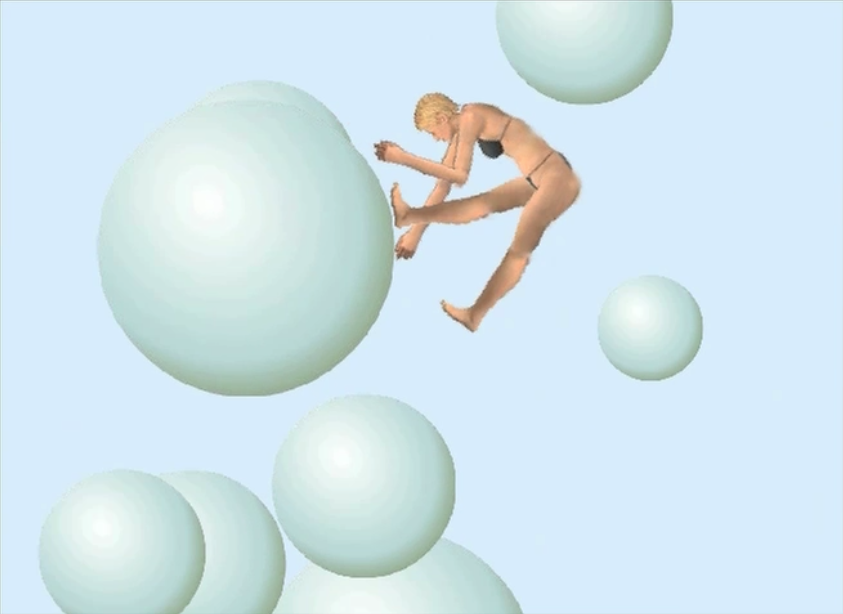

Freya Olafson’s 2013 performance work HYPER_ actively plays with images of the posthuman cyborg body in the digital age. HYPER_ features a mix of live dance, digital arts, 3D animation, UV light and large scale projections that absorb the dancer in a series of transformations. The screen is immersive, working to combine virtual bodies with Olafson’s live, organic dancing body and enact a spectacle of disembodiment, or rather, a striptease that reveals a “body” made of muscle and bone, in several stages. Olafson’s work comments more directly than Fuller’s on the role of gender in relation to new technologies, largely in part because Olafson is creating over a century after Fuller, at a time in which feminist approaches to art-making are much more commonplace. In HYPER_, the somatic feminine presence is fetishized alongside technological objects and processes, and Olafson’s body mutates from material human canvas, upon which information is displayed, to an entity at one with that very information. Throughout HYPER_, Olafson projects filmed images of her body onto the screen behind her in order to produce the effect of multiple selves7. Near the end of the piece, Olafson emerges from the wings having painted her limbs, torso and face with glow-in-the-dark paint to resemble a skeleton. When viewed in darkness, and with the 3D glasses provided, the rest of Olafson’s human body melts away and the audience is left alone with her performative skeletal form, which, aided by a projection, has now multiplied by three. When she dances with her skeleton clones, they are like a balletic trio in perfect unison; Olafson has done away with the involuntary clumsiness of the human form in favour of a perfectly programmed and synced alternative. Her simulacra counterparts are both completely her yet also separate from her, presenting multiple embodiment as an alternative to the human being as a discrete or unique entity, in keeping with the aesthetics of posthuman dance.

Later in the show, a projection features a series of multiple copies of the same choreographic clip, timed sequentially and at a lag, to give the effect of Olafson’s body leaving itself. The imagery pays homage to Norman McLaren’s NFB classic Pas de Deux (1968), and as such, Olafson extends the notion of multiple embodiment to include the cinematic bodies she references with her gestures and techniques8. In this way, the dance body becomes a referencing machine, which always carries with it the trace of past movement, demonstrating that cyborg identity need not leave the body behind. Yet despite these moments of “worlding” that occur between and across bodies, HYPER_’s primary theme, as conveyed through Olafson’s nuanced presentation of various states of (dis)embodiment, seems to be centered on the erasure of the female body.

Like Fuller, Olafson uses her body and costuming to produce an animated screen. Just as Fuller was pioneering in the emerging field of electric light, Olafson, who holds an MFA in New Media from the Transart Institute / Donau Universität in Austria, is responsible for designing and programming the technics of her own shows. Like Fuller, Olafson fashions herself into a dancing cyborg. However, whereas Fuller’s body became more obscured over the course of her show, engulfed in moving folds of heavy fabric, Olafson’s HYPER_ parodies the performance of a striptease, in which her nude body is only an afterthought, a decoy for the real, technologically-enhanced, attraction. This approach is evident from the start of the show, at which point we see a projection of footage from a video game in which the goal, it seems, is to get a bikini-clad avatar to perform a pole dance. The animated dancer stands obstinately by her pole, wagging her hips to the music as the gameplay cues pass by and refusing to perform; the male voice of the narrator announces: “I smell bad pole dancing.” Directly following, the lights come up on Olafson. She is wearing a black strapless dress that fragments her body by highlighting her chest, arms and face and erasing her torso into the black scrim behind her. Olafson moves through a series of sexualized and mechanical poses, stopping now and again to put two fingers to the inside of the opposite wrist. She checks her pulse to remind us of the thin line between her living body and the animated female form we just saw on screen.

Throughout the show, live dance is interspersed with projections of animated female bodies. Some of this is found footage, and some of it, like the clip titled “Release Technique,” was created by Olafson in a “keystroke choreography” using a movement study game interface. The female body in this virtual choreography is manipulated by the player through keystrokes in order to facilitate her free-fall, maneuvering her around and between large round obstacles that block her path. The digital woman is disturbingly corpselike (her eyes are closed and her limbs are limp) and, again, dressed in overtly sexual attire (a black string bikini). As she falls through virtual space, her body goes through a series of violent transformations. She is bent in half, her joints are hyperextended, and her face ricochets off of the blunt objects as she hits them. Her inhuman flexibility gestures towards an objective of ultimate maneuverability. Furthermore, her fall appears endless, with no endpoint, suggesting an infinite infliction of brutality upon this virtual body. By including such images in her show, Olafson demonstrates that digital-era fantasies of somatic-enhancement via technology are often matched by fantasies of violence, centered on women’s bodies. This footage serves as a constant reminder, throughout HYPER_, that this spectacle has a gender.

Olafson satirizes the notion of disembodiment as a kind of erotic striptease, inhabiting various states of “undress” which allow her to shed recognizably feminine epidermic features in favour of a genderless science-body. These include a bodysuit printed with human musculature and a glow-in-the dark skeleton body painted directly on the skin of her torso, limbs and face which, when lit by blacklight in darkness, looks alarmingly realistic, producing a result is both humorous and uncanny. The intermittent use of strobe light in this sequence highlights Olafson’s naked body just briefly, in a harsh white flash, so that her human form becomes a ghost within the assemblage, a naked distraction amid the skeleton trio dreamscape. We are offered brief glimpses of her humanness — her real breasts, her pubic hair — beneath the two dimensional, frenetic skeleton that masquerades as her, but by the end of the show there is no trace of human left.

Symbol: “Made Visible By an Artifice”

HYPER_ closes with a sequence that features a set of swirling red and blue rhythmic gymnastic ribbons. Operated by Olafson’s unseen hands, the ribbons dance fluidly, diving and skipping along the ground, swirling up into rogue pirouettes and leaps. We know Olafson’s body is still there, working hard at making these materials expressive, but because her body is hidden in the blackout, we are able to imagine that the ribbons have their own agency. The effect of this displacement, which projects the labour and magic of Olafson’s invention onto the dehumanized material, is much like that of Loïe Fuller’s stage shows: the symbolic image usurps the particulars of the body.

Fuller’s work is often associated with Symbolism, the late-nineteenth century European arts movement which rejected realism in favour of spirituality, imagination and dreams to better represent anxieties about the influx of new technologies at the time. Her work was thought to be Symbolist because of its ability to blur the lines between illusion and reality—an effect described by famous Symbolist poet Stephane Mallarme as “the dizziness of soul made visible by an artifice.” (Rancière, 2007) Fuller’s gender, or rather, her ability to transcend her gender, was also key to her role as the Symbolist’s muse. In “Ballets” (1886), Stéphane Mallarmé writes:

“the ballerina is not a girl dancing … she is not a girl, but rather a metaphor which symbolizes some elemental aspect of earthly form: sword, cup, flower, etc., and that she does not dance but rather, with miraculous lunges and abbreviations, writing with her body, she suggests things which the written work could express only in several paragraphs of dialogue or descriptive prose. Her poem is written without the writer’s tools.” (Mallarmé, 1976, p. 94)

In his aesthetic abstraction of the dancer, Mallarmé demonstrates that in his view, the dancer’s body is also prosthetic to the imagery she is capable of evoking. As Amy Kortiz writes, “[t]he dancer’s agency has at best a precarious place in [Mallarmé’s] formulation, since she is text, writing implement and meaning all at once, while at the same time not being a subject, who could write.” (Anderson, 2008, p. 355) Fuller’s work was often described using spectral terms such as “unique, ethereal, [and] delicious.” (Gunning, 2003, p. 79) She was called a “magic blossoming,” a “whirlwind of light and veils…vanishing and disappearing like a pale mist,” (Lista, 1994, p. 25) and a “lovely apparition.” (Gunning, 2003, p. 79) Reviewers in Paris and New York constantly referred to her in ephemeral rather than material, human terms; Fuller was not even a body in motion but rather, motion itself.

Given that Fuller came to exemplify such an array of abstract and philosophical conceptions, and that she is often described in inhuman, even immaterial, terms, it is easy to forget that she was also just a woman, dancing in front of an audience9. Her female body still bore the objectifying gaze associated with spectacle, whether dancing on stage or screen. In fact, many of Fuller’s fans were surprised by the shape and size of her body when they saw her offstage, in normal lighting, and there she was, a “rather plan-looking girl from Illinois.” (Sutton, 2012) There was a contrast between the “highly eroticized body” portrayed on Fuller’s publicity posters and her real, “rather pudgy” body. (Gunning, 2003, p. 84) Despite the dehumanized spectacle she presented on stage, Fuller was well-known to her audience, who was very familiar with her eroticized body, as established during her vaudeville career. It can be argued that her skirt dance was all the more beguiling because it actively excised these past versions of Fuller, the woman.

The sexualized female body is the ghostly signifier in both Fuller and Olafson’s work – the non-presence that announces itself in its absence. In erasing the fetishized image of a “girl, dancing,” these artists ask us to question the politics of our own persistent desire for the dehumanization of art.

Conclusion: Return to the Body

The aesthetics of intermedia dance can often be mapped onto the aims of posthumanism; both practices acknowledge the power of technologies to produce new understandings of subjectivity and embodiment rooted in hybridity, extension and dispersed agency. Yet the problem, as I see it, is that as important as it is to expand ethics and politics beyond the human as discrete entity (with intermedia arts acting as a useful platform for exploration of new bodies and identities), in slotting “the human” into one category of sameness, this proposition does not acknowledge the multiplicities that already exist within said category. To hybridize and transform “the human” is a dream rooted in imagined possibilities but these possibilities are often represented aesthetically as a flight from the body, what Susan Bordo calls the “view from everywhere.” Bordo writes that in order to achieve “human freedom from bodily determination” we have metaphysically deconstructed the body in the digital age into a fantasy “ideology of limitless improvement and change [that defies] the historicity, the mortality and, indeed, the very materiality of the body.” (Bordo, 1993, p. 245) This fantasy of limitless multiple embodiments, Bordo argues, is just another kind of disembodiment: in her words, “the postmodern body is no body at all.” (Bordo, 1993, p. 229)

Of course, some may say that in enacting a continuous set of transformations on the body, Fuller and Olafson demonstrate the true nature of embodiment as a “highly complex and fluid state, at odds with a psycho-social imaginary that privileges corporeal wholeness and integrity.” (Shildrick, 2018) Philosophically, we know that the image of corporeal wholeness is a fantasy, especially in the digital age in which our consciousness is split and fragmented across screens and different modes of interaction. In my research, I have found that traditional definitions of dance often align with fantasies of disembodiment similar to those we imagine new and interactive technologies might facilitate. In Time and the Dancing Image (1988), American dance historian Deborah Jowitt writes of the weightless, supernatural quality prized by classical dance in the romantic era where “insubstantiality [was] close to godliness.” (Jowitt, 1988, p. 39) Dancers were praised not so much for their physical prowess as for their ability to look and move in an angelic fashion. Jowitt remarks that the female dancer in particular was a creature of paradox in that she was seen as both a poetic image and a “panting perspiring body.” (Jowitt, 1988, p. 39) The frequent use of the word “freedom” in descriptions of dance’s aim is striking, and also points to the sexist impulse to wish away the abject corporeality of the (often) female dancer. Susanne Langer argues that “the most important [force], from the balletic standpoint, is … the sense of freedom from gravity” (Langer, 1953, p. 43) as does Paul Valéry, who writes that in dance, the body seems to have “broken free from its usual states of balance. It seems to be trying to outwit—I should say outrace—its own weight, at every moment evading its pull, not to say its sanction.” (Valéry, 1983, p. 60) In the words of French poet Théophile Gautier in the mid-1800s, dance is “essentially materialistic and sensual.” (Copeland, 1983, p. 52) To the dancer, dance is a felt physical sensation, to the viewer, dance is an image. In the topic of dance on stage, the image of the body, and the spectator’s relationship to that image, takes a primary importance. The images given to us by Fuller and Olafson’s performances are just as powerful as the tools they use to get there.

Loïe Fuller’s theatre shows, which featured a “dark and bare stage” upon which her “body and veils [were] splashed with coloured light,” can be considered a precursor to cinema pre-1907, an era Gunning terms the “cinema of attractions,” in which the body on stage or screen is the “entire spectacle.” (Gunning, 1986, p. 63-70) Films such as the first Edison Kinetoscope projects, which played “within shallow spaces, [and were] often shot against a darkened background,” directed the viewer’s focus to the “direct stimulation” of non-narrative spectacle (Gunning, 2003, p 66). In using the “cinema of attractions” to think about Fuller and Olafson’s work, I wish to draw attention to the ways in which “attraction” is rooted in the visual spectacle of feminine disembodiment. Or rather, the way in which the “attraction” of the female body acts also as vehicle or screen for a process of transformation away from the human form. Hopeful ideas about hybridity and distributed agency, common to discourses of new materialism, posthumanism, and techno-utopian approaches to making art with technology need to be balanced with an awareness of the ways in which such approaches can also hinge on concepts of purity or neutrality, which seek to erase unique, lived experience in favour of an abstract, symbolic body. Karen Barad writes that “posthumanism marks a refusal to take the distinction between ‘human’ and ‘nonhuman’ for granted, and [founds its] analysis on this presumably fixed and inherent set of categories,” (Barad, 2003, p. 801-831) but too often the category of woman (which is already considered less than human by some) is the stage upon which this collapsed binary performs itself. As Donna Haraway writes, “urgent work still remains to be done in reference to those who must inhabit the troubled categories of woman and human” before we can move past those categories in any significant way (Haraway, 2008, p. 17). Fuller and Olafson’s gender is crucial to the way we read their performances. While technologized dance can sometimes appear to desire a posthuman (and post-gender) utopia, it is precisely the erasure of the gendered body, and the thrill therein, that should give us pause about such utopian pursuits.

Notes

[1] Viewers of the video linked here should keep in mind that film footage of Fuller’s dances were hand-tinted in post production to attempt to portray the colourful effects of her liver performance.

[2] For feminist interpretations of Loïe Fuller’s work, see also Erin Brannigan, Dancefilm: Choreography and the Moving Image, Oxford University Press, New York, 2011; Elizabeth Coffman, “Women in Motion: Loïe Fuller and the “Interpenetration” of Art and Science,” Camera Obscura, vol. 17, no. 1 (2002), p. 72-105; Tom Gunning, “Loïe Fuller and the Art of Motion,” Camera Obscura, Camera Lucida, Eds. R. Allen and M. Turvey. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2003, p. 75-89; and Dana Mills, “The Dancing Woman is the Woman Who Dances into the Future: Rancière, Dance, Politics,” Philosophy & Rhetoric, vol. 49, no. 4 (2016), p. 482-499.

[3] Although I use terminology such as “the body” and “the female body” in this paper, I do not wish to invoke “the body” as a generic object of study, as it is precisely the distinctions among bodies that need to be grounded conceptually and historically. Whenever possible, I will attempt to use specific terms in relation to Fuller and Olafson’s corporeality, while also acknowledging the power of the “female body” as generic cultural signifier in my analysis.

[4] See, among others, Johannes Birringer, Performance, Technology and Science, New York: PAJ Publications, 2008; Susan Kozel, Closer: Performance, Technologies, Phenomenology, Leonardo Books, Cabridge: MIT Press, 2008; and Sophie Walon, “Corporeal Creations in Experimental Screendance: Resisting Sociopolitical Constructions of the Body.” In The Oxford Handbook of Screendance Studies, Ed. Douglas Rosenberg, New York: Oxford University Press, 2016, p. 321-348.

[5] Erin Manning, for example, has written that “The complex analog body is reduced by the prosthetic system to a passive interactivity, forced to conform to a pre-established definition of what a body can do. The body must move for the software” (in “Prosthetics Making Sense: Dancing the Technogenetic Body,” The Fibreculture Journal, issue 9, 2006, http://nine.fibreculturejournal.org/fcj-055-prosthetics-making-sense-dancing-the-technogenetic-body/).

[6] Quoted in Brannigan, p. 32.

[7] Similarly, Loïe Fuller’s “Mirror Dance,” in which her placement of four mirrors in a semi-circle behind her on stage gave the synthetic appearance of eight figures dancing in unison, used a more analog “technology” to experiment with images of multiple embodiment and distributed agency.

[8] Between 1895 and 1905, Fuller’s magical performances were copied and repeated by other dancers such as Ameta, Chrissie Sheridan, Annabelle, Ruth St. Denis and Émilienne d’Alençon, Given her many imitators, Loïe Fuller’s work can also be said to reference (or be referenced by) other bodies through time and space.

[9] One reviewer remarked that the audience must insist “upon seeing her pretty piquant face before they can believe that the lovely apparition is really a woman.” In Sally R. Rommer, “Loïe Fuller,” Drama Review, vol. 19, no. 1, (March 1975), p. 53-67.

Bibliographie

– Anderson, Elizabeth, “Modernism: Ritual, Ecstasy and the Female Body,” Literature and Theology, vol. 22, no 3, septembre 2008, p. 354-367.

– Barad, Karen, “Posthumanist Performativity: Toward an Understanding of How Matter Comes to Matter”, Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society, vol. 28, no 3, 2003, p. 801-831.

– Bordo, Susan, Unbearable Weight: Feminism, Western Culture, and the Body, Berkeley, University of California Press, 1993, 361 p.

– Gunning, Tom, “The Cinema of Attractions: Early Film, Its Spectator and the Avant-Garde,” Wide Angle, vol. 8, no3, 1986, 63-70.

– Gunning, Tom, Art of Motion, Amsterdam, Amsterdam University Press, 2003, p. 75-90.

– Haraway, Donna, “A Cyborg Manifesto: Science, Technology and Socialist-Feminism in the Late Twentieth Century”, dans Simians, Cyborgs and Women: The Reinvention of Nature, New York, Routledge, 1991, p. 149.

– Haraway, Donna, When Species Meet, Minneapolis, University of Minnesota Press, 2008, 440 p.

– Jowitt, Deborah, Time and the Dancing Image, Berkeley, University of California Press, 1988, 184 p.

– Langer, Susanne K., Feeling and Form: A Theory of Art Developed from Philosophy in a New Key, New York, Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1953, 431 p.

– Lista, Giovanni, Loïe Fuller: Danseuse de la Belle époque, Paris, Stock Somogy Éditions d’Art, 1994, 682 p.

– Mallarmé, Stéphane , “Ballets,” Salmagundi, no 33/34, 1976, p. 92-97.

– Merwin, Ted, “Loïe Fuller’s Influence of F.T. Marinetti’s Futurist Dance”, Dance Chronicle, vol. 21, no. 1, 1998, p. 73-92.

– Rancière, Jacques, The Future of the Image, Trans. Gregory Elliott, New York, Verso, 2007, 160 p.

– Shildrick, Margrit, “Re/membering the Body,” dans Asberg, Cecilia et Braidotti, Rosi, A Feminist Companion to the Posthumanities, New York, Springer, 2018, 245 p.

– Sutton, Anne, “Infinite Light: The Dance of Loïe Fuller,” The Australian Ballet, 23 mars 2012, en ligne, <https://australianballet.com.au/behind-ballet/infinite-light-the-dance-of-Loïe -fuller>

– Valéry, Paul, “Philosophy of the Dance,” dans Copeland, Roger et Marshall Cohen, What is Dance?, Oxford, Oxford University Press, 1983, p. 55-65.