In 2013, Goosan Artistic Group, an Iranian group of performance artists, created a promenade performance based on Euripides’s Hippolytus, in which the spectator became the actor, the actor became the director, the video installation became the corpse, and all of them together stood witness to a performative moment of history: Hippolytus awaiting his verdict in Tehran. The first encounter between the spectator and the character takes place at the very beginning of the promenade. The hyper-real mask of Hippolytus’s dead face can be claimed by each member of the audience. And that is how Goosan, this small group of four young Iranian performers, call their audience to bear witness to the memory and trauma of a historic character reborn in their country, on their stage, among them.

In this essay, I investigate the transformation that the body of actors go through when confronted with a multitude of technologies—video art, sculpture, surveillance technologies, and in-time-video projection—and the ways in which acting techniques are revisited by the performers. I shall do so by acknowledging the following characteristics in the performance: Throughout the course of the performance, the audience is given the choice of experiencing death by lying on Hippolytus’ death-bed, or putting on his mask, and finally by voting for his destiny, while interacting with the two actors, the director, and the assistant director. Offering the possibilities that are presented through various technologies utilised in the performance, Hippolytuschallenges its spectator, at once physically and mentally. The four members of the team are from the generation who has experienced a failed election and a failed uprising; they have experienced the consequences of decisions made for them by a government they cannot trust. Yet, they are the generation of social networks and virtual reality. Therefore, in this paper, I shall argue how, through practice of their everyday life performances, they have created a performative palimpsest of the topology of cultural memory, virtual reality, technologies, and aesthetics.

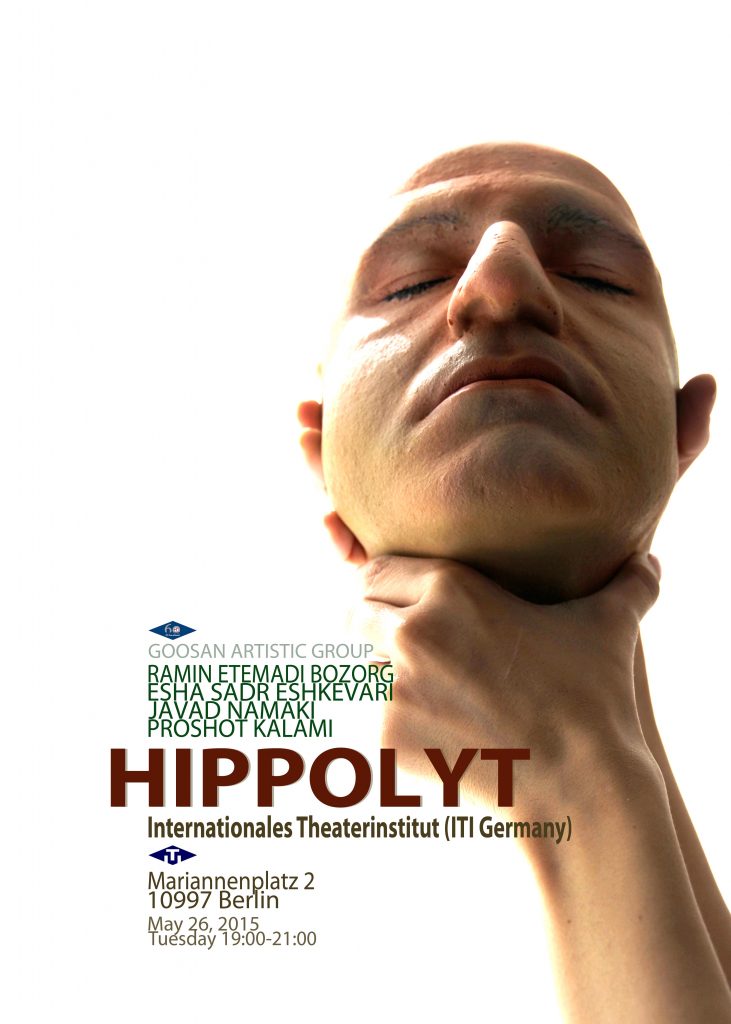

In 2013, the Goosan Artistic Group, a four-person troupe of Iranian performance artists, created a performance loosely based on Euripides’s Hippolytus, in which the spectators became the actors, the actors became the directors, the video installation became the corpse, and all of them together stood witness to a performative palimpsest of cultures. They named it “Hippolyt.” In what follows, I shall call it “the Persian Hippolyte.” The tripartite structure of this performance consists of the text, the body, and the technology. This Persian Hippolyte performs a real-life manifestation of democracy – that is, exercising the right to vote. It also draws on the politics of the courtroom, calling upon the audience to judge and to vote. For the act of judgment lies at the heart of all three versions of the myth that inspired this performance.

In addition to the Greek tragedy, there are two legends on the same theme. The Greeks tell us how Hippolytus was killed after rejecting the advances of his stepmother Phaedra (second wife of Theseus), and how Phaedra framed Hippolytus in a suicide note indicating that he raped her, thereby inciting Theseus’s curse, which led to Hippolytus’s death. The biblical story tells of Potiphar’s unnamed wife, who is rejected by Joseph, a slave to her husband, the Pharaoh’s general. A medieval commentary on Torah, however, names her Zuleikha, as does the Islamic tradition–hence its appearance in the Persian poem “Yusuf and Zulaikha” from Jami’s Haft Awrang (aka Seven Thrones)1. In the Persian world, a ceremony is held in remembrance of the undeserved killing of Siavash, the Kayanid Prince who suffered a tragic and untimely death. According to scholars, “The story of Siavash revolves around a young prince characterized by his high morality, heavenly looks, and chivalry,” (Daryaee, 2014, p. 57) who rejects the advances of his stepmother, and is thus framed by her to be condemned to exile, leading to his death.

In May 2015 at Berlin’s International Theater Institute Deutschland, Goosan Artistic Group and I had a workshop presentation of Hippolyt. In the Q & A, when the members of the group explained their way of realizing the performance, it was apparent that they were leaning more toward the concept of “innocence” in the tragic figure, while the whole dynamics between him and the enamoured stepmother is pushed aside. When the participants were asked why this was so, their answer appeared gradually, in a meandering path that I hope to explain within the course of this text.

This is how our Persian Hippolyte embarked on a journey leading to his “verdict” in Tehran, then in Paris, and finally in San Francisco in 2014. He was supposed to be “judged” once more in Tangier. But alas, Poseidon sent the bull to stop him from getting the visa to traverse the sea. (The politics of staging outside its borders a performance originating in Iran is a different issue in itself.)

The Persian Hippolyte aims to foreground the physical relationship between the bodies of performers and spectators, both of whom are confronted by various types of media and technology. The first “encounter” between the spectator and performers takes place when the spectators arrive outside the space of performance. While the performance does not claim to be a documentary, the Persian Hippolyte “documents” its audience in an initiation process, before they are allowed entry into the performance space. This initiation process is considered as part of the performance.

In the initiation, each spectator is handed Hippolyte’s death mask, to put on and be photographed. A slide show of these pictures will be played for the duration of the performance, on a monitor visible to the audience. Spectators are then led to a deathbed. If they are willing, they can lie down like a corpse and be photographed and documented. The reaction was varied. The Tehran audience went through the process without question, leading to a 45-minute performance. In Paris, during the registration process, the audience questioned, objected, or interrupted, resulting in a 99-minute performance. The California audience objected to being the finger-printed, leading to a one- and a two-hour performance. Thus, to borrow a term from Gérard Genette, “extradiegetic,” (Genette, 1980) non-mise-en-scène factors arising from the place of performance (Teheran, Paris, San Francisco) inform the performance. These factors are completely beyond the control of performers and performance. The 2015 Berlin workshop participants also had their own unique reaction to this process. Some refused to be fingerprinted; some did not want to be photographed; some found the deathbed comfortable and relaxing rather than unnerving. These led to an interesting Q&A session, which I believe offered insights capable of changing the nature of the Persian Hippolyte in future performances.

This is how the Goosan Artistic Group calls upon its audience to stand witness to the memory and trauma of a historic character reborn in their country, on their stage, among them. The spectators are shown the secret of the tragic hero, and then must vote upon his destiny, which has already been decided. They are compelled to exercise their democratic right. After all, they are registered and documented. Yet, the decision has been already made.

In what follows, I will investigate the transformation that the body of performers / spectators go through when confronted by a multitude of technologies (video art, sculpture, surveillance technology) and the ways they inform the mise-en-scène. While interacting with performers, the audience is given the choice of experiencing death by lying on Hippolyte’s death-bed, or putting on his mask, and finally by voting on his destiny. Offering these possibilities through various technologies used, the Persian Hippolyte challenges its spectators, both physically and mentally. The four members of the Goosan team are from the generation that has recently experienced a failed election and a failed uprising. They have felt the consequences of decisions made by a government they cannot trust, and of political powers in a world they are not part of. Yet, they are the generation of social networks and virtual reality, of iPads and smartphones and apps, who document their every gesture and experience in selfies or photos sent into the virtual world. Clearly, technology is one of the primary means of transmitting knowledge. Hence I am trying to see how, through performing the practices of everyday life, the Persian Hippolyte has created a performative palimpsest of cultural memory, virtual reality, technologies, and aesthetics, through bodily encounters among its performers and members of the audience.

Within the performance space of Hippolyte there is a métissage of the semiotics of the body and the aesthetics of media and technology. This is at the core of the production’s genesis. Let’s call it “acting confronted by contemporary media and technology,” since performing bodies have always been working with, against, or alongside technology. Métissage, as Couchot acknowledges, is “a permanent and more or less assertive feature of art2.” He continues to value the métissage of technologies involving sound and image with non-digital ones as the “cornerstone of multimedia,” and places it within the realm of performance art. What is more significant here, I believe, is the use, the methodology, the effect, and the ways in which it interweaves with other components of the performance. In the Persian Hippolyte, media and technology, regional cultures, historical cultures, dramatic cultures, and the practice of everyday life are all tightly interwoven. According to Couchot, this allows the performance to radically transform the relations of the body and technology. “It associates a ‘human subject’ and a machine in an intimate way and sets up an absolutely unprecedented relationship between man and man-made automatic artefacts3.” Unraveling this relationship demands the following explorations: looking at the performance as a documentary; looking at the bodily interaction between performers and audience within the context of Greek tragedy (particularly between the chorus and the individual); looking at the media and technology utilized within the mise-en-scène; and finally, looking at how technology informs the performance as a whole, and the bodily interaction in particular.

Technology is used here as evidence, as a means to interfere, to support, and to do what it does in real life. That is, it enables the communication of particular information, and at the same time to creates a sense of discomfort, lack of control, displacement, and agitation. These effects vary depending on the audience, their personal and collective experience, and, no doubt, their nationality and sense of belonging.

The use of technology in the Persian Hippolyte indicates that the human condition is ephemeral. In tune with Adorno and despite the utopian ideal expressed in the “promesse du bonheur,” (Adorno, 1999, p. 311) it establishes the fact that in order to recreate real life, the performance has to betray that reality. And it does so with its use of technology and media. In this performance the actors use technology to rebel against the hegemony of the chorus–i.e., the body of the audience.

It is impossible for the spectators to remain in the traditional position of theater observers. Audience participation begins as soon as the spectators enter the space. This entrance or prologue is a devised ritual. In it, through the process of documentation, identification, photographing, and experiencing the deathbed, each audience member is repositioned in his relationship to the other spectators and the actors, and to the action taking place. During the first two stages of the performance at least, the performance takes place in the space between the audience and the performers, and between the chorus and the performers; there are moments when the audience even becomes the performer. In my view, technology promotes these moments when Hippolyte rebels against the hegemony of the chorus, responding instead to the human condition and the ephemerality of relationships between the body of the actor and the audience. As Erika Fischer-Lichte states, “through their physical presence, perception, and response, the spectators become co-actors that generate the performance by participating in the ‘play,’” (Fischer-Lichte, 2008, p. 32) thus challenging the classic relationship between the audience and the performer as well as that of the chorus with the actor(s).

She also says, “Nietzsche claimed that the chorus is the origin of theater, and tragedy is constituted by the incessant battle between two conflicting principles: that of individualization and that of its destructions, or dismemberment.” (Fischer-Lichte, 2005, p. 245) The Persian Hippolyte recreates tragedy on its stage by violating the chorus. It violates its spectator / chorus, physically and emotionally. For example, almost half way through the performance, one of the performers cuts onions onstage but in close proximity to the spectators, while a screen projection shows cutting liver and heart.

The other example is when members of the audience choose to lie down on the deathbed. Inside the pillow there is a microphone. When they put their heads down and are covered by the burial cloth, they suddenly hear a religious chant that is used at the moment of placing the corpse into the grave. And the final jolt is when the audience casts its vote. The ballots given to them are in two colors – green and yellow. One color indicates a vote to exonerate Hippolyte, the other to condemn him. These are dropped into a blue glass box, with the result that all papers appear to be the same color. Hence votes lose their value. Either way, Hippolyte must die. He is the sacrifice for the community’s survival.

Sacrifice in a community can create a sense of unity. But here the community, represented in the idea of the chorus/audience, is constantly disturbed by the mediation of technology and by the interchanging roles between performer and spectator. Therefore the “incessant battle between two conflicting principles” (Fischer-Lichte, 2005, p. 245) reinstates the tragic in tragedy. The Persian Hippolyte may be seen as a political expression against a verdict, informed by current socio-political events. But fundamentally, it foregrounds the tragic and ephemeral human condition, when the question of judgment is involved. In real-life situations, the forensic evidence gathered and stored on a case can be as conflicted as in the case of Hippolyte. There is a constant struggle between the individual (Hippolyte) and the chorus. This is not simply a representation of a motif from the Greek tragedy, but a process repeated every day when judgment or voting is involved. The chorus / audience can assume the position of the prosecution or the defense. In the biblical legend, the tragic hero is eventually rewarded for his piety and belief.

The Greeks and Persians take a different view. Yet whether they support or discredit Hippolyte’s case, the outcome is the same. The Greeks send Artemisia to clear his name (he dies anyway), and thus to allow the community to be restored by this noble sacrifice. The Persianites, on the other hand, lament the unjust death of their tragic hero in community mourning, and pay less attention to questions of desire and lust. In both cases, acts of sacrifice allow the community to be built. The Persian Hippolyte dismantles the chorus, the community, and the hegemony of the audience through its use of technology and mise-en-scène, thereby challenging the formation of community through Hippolyte’s sacrificial death. This is in keeping with what Fischer-Lichte has said: “individual and community cannot be conceived independently of each other. There is an ongoing battle between the two but it is a battle, which can never be won. It must continue for ever – i.e. as long as human society exists.” (Fischer-Lichte, 2005, p. 249) She continues:

A sacrifice is unable to uphold the community. Society can only exist as a permanent conflict between individual and community. Such conflict may only be settled temporarily. […] It [harmony] emerges unforeseen and unpredictably – as a result of fortuitously uniting energies, which may split up again and confront each other the very next moment. It is not sacrifice, nor common beliefs, ideologies, convictions, ideas, commonly performed actions, nor shared experiences that are able to bring forth a community. It is […] an anthropological necessity, which drives individuals to form a community as well as uphold their own individuality at the same time. The one cannot do without the other, although both are constantly threatened by the existence of the other. There is no way out of this constellation. A “viable dialectic between solitude and being-with-others” is inconceivable. (Fischer-Lichte, 2005, p. 249-250)

In order to recognize this relationship, we must question the mediation of the technologies that define the space of the performance, and the ways in which they can or cannot render the body of the actor any performative scope and / or layer. The mise-en-scène forces the audience to become actors who can claim a subject position for themselves, which simultaneously objectifies them and the other. For example, a spectator assumes the role of the corpse going through the ritual of burial preparation by one of the actors. This puts the spectator in the position of subject, while she or he is simultaneously objectified by the real actor who is now the other. The subject and the object can no longer be clearly defined and distinguished. As Fischer-Lichte acknowledges, “the staging strategies or games” devised for a performance such as Hippolyte

constantly play with three closely related processes: first, the role reversal of actors and spectators; second, the creation of a community between them; and third, the creation of various modes of mutual, physical contact that help explore the interplay between proximity and distance, public and private, or visual and tactile contact. Despite the large diversity of these strategies […] they all have one feature in common: they do not – if at all – simply depict role reversal, the creation and collapse of communities, proximity and distance. Instead, they actually create instances of these processes. The spectators do not merely witness these situations; as participants in the performance they are made to physically experience them. (Fischer-Lichte, 2008, p. 40)

The question here is if the Persian Hippolyte aims to create the communal sense with its mise-en-scène and use of technology, or does it aim to challenge the notion of community? What is the experience that Hippolyte suggests? I hesitate to claim that this participation can eventually turn into a social event. It is hard to say whether the audience can form a community or not. It is an experience which, depending on the audience, geography, national and regional cultures, histories, and the geopolitics of time, can vary. But what remains a fixed factor is that the performance is constantly informed by the negotiation of positions and by shifting power relations. It demonstrates to every participant that the act of perceiving the other is always a political act. This is not limited to the “documentation” process upon entry. The performance allows and provokes discrepancies. The ambiguous spatial set-up can always interrupt any sense of unity there might be. Upon arrival, the audience does not know if they are dealing with actors or not. This is further challenged by the use of technology in the production.

The distinction between live events and mediatized events is collapsing more and more these days, since the real event, or the practice of everyday life, is becoming more and more mediatized. Our contemporary generation is the most documented one of all time, due to the existence of Androids, smartphones, and iPhones. This creates an intimacy and immediacy that is only possible because of the technology. Hippolytesuggests a spatial intimacy that is very much inspired and informed by such phenomena. Hence distinguishing a live event from a mediatized performance4 is so tenuous now. The argument should not be over the superiority of one over the other. The question(s) instead must concern the culture of performances defined, informed, nuanced or controlled by varying degrees of technology.

Can the Persian Hippolyte survive the test of cultures and expectations? The reaction of the Berlin audience in May 2015 indicated that the workshop performance assumed too much liberty in imagining audience participation. The artists said they wanted the audience to be as free as possible in participating (or not participating), and in reacting in whatever way possible. This created a heated discussion during the Q&A session. What emerged was this key insight: Young Iranian artists who had lived all their lives under a religious dictatorship were ready to imagine a great degree of freedom in their spectators’ reaction. They imagined their performance would present the participants with more freedom of thought and action than they had ever experienced. Hence they let the possibilities of interaction among media / chorus / audience / performers be decided at the moment, in situ. Although this may be a problematic approach to realizing a performance, it is an indicator of the courage of these Persian performers. What Hippolyte offers beyond this is the bodily co-presence of performers and spectators—a co-presence that cannot be grasped, understood, or experienced without technology. This is because the Persian Hippolyte is all about the “presentness,” the everyday life, the everyday judgment, the contemporary human condition: “What the spectators see and hear in the performance is always present. Performance is experienced as the completion, presentation, and passage of the present.” (Fischer-Lichte, 2008, p. 94) In the contemporary Iranian imaginary, this may well give a chaotic notion of freedom, reflected at times in the structure of the performance we witnessed in Berlin.

Notes

[1] “Joseph,” Encyclopedia Britannica, <http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/306324/Joseph>. Also note that in a conversation with the artists, they said they were not really thinking about this version of the story. However, it is interesting to observe that both in the Islamic version and in the performance of Persian Hippolyte, the role of the stepmother / seductress, is pushed to the side and is not really regarded as an important element. The limelight is on the antihero, Hippolytus / Joseph.

[2] Couchot, Edmond. “Media Art: Hybridization and Autonomy,” <http://www.mediaarthistory.org/wp-content/uploads/2011/05/Edmond_Couchot2.pdf>.

[3] Ibid.

[4] See Erika Fischer-Lichte’s analysis of the famously antagonistic points of view asserted by Philip Auslander and the Peggy Phelan in: Fischer-Lichte, Erika. The Transformative Power of Performance, Chapter 3 “Shared Bodies, Shared Spaces. The Bodily Co-presence of Actors and Spectators,” op. cit., p. 38-74.

Bibliographie

– Adorno, Theodor W, Aesthetic Theory, Londres, Athlone Press, 1999, 416 p.

– Couchot, Edmond, «Media Art: Hybridization and Autonomy», en ligne, <http://www.mediaarthistory.org/wp-content/uploads/2011/05/Edmond_Couchot2.pdf>.

– Daryaee, Touraj et Soodabeh Malekzadeh, «The Performance of Pain and Remembrance in Late Ancient Iran», The Silk Road, vol. 12, 2014, p. 57-65.

– Fischer-Lichte, Erika, The Transformative Power of Performance: A New Aesthetics, New York, Routledge, 2008, 240 p.

– Fischer-Lichte, Erika, Theater, Sacrifice, Ritual: Exploring Forms of Political Theater, New York, Routledge, 2005, 304 p.

– Genette, Gérard, Narrative Discourse: An Essay in Method. Ithaca, New York, Cornell University Press, 1980, 288 p.

– Joseph, Encyclopedia Britannica, en ligne, <http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/306324/Joseph>.