Literally « a place to observe, » the « theatron » has been an experimental platform for optical technologies, and, more recently, for cameras and projection devices. Integrating live video on the contemporary stage not only facilitates the actor’s performance, it often functions as an extension of vision, opening up multiple perspectives by introducing cinematic principles of framing, montage and different dimensions of time and space. This paper, however, will discuss the role of the video camera as an object of inquiry.

Through an analysis of experimental performances by young Brussels-based media and performance artists, I will demonstrate how the status of the performer and his/her relation to the camera radically shifts, when enhanced by the use of live video, from an actor embodying a character to a lecturer-performer, dissecting the apparatus of vision. The camera in the work of the artists whose practices I will chart, is no longer a medium for the actor’s play, but becomes the objective itself. Theatres become laboratories for exploring regimes of seeing. In a setting reminiscent of « The Anatomy Lesson » (one of the original sites for the construction of modern spectatorship), Julien Maire literally dissects and amputates cameras and other optical machines (Open Core 2009). With Point of View (2013), choreography for dancers, cameras and projection, Benjamin Vandewalle explores questions of kaleidoscopic perception, movement, and distinctive simultaneous viewpoints. With this renewed interest in visuality, these artists explore the potential and limits of perception, thereby examining how seeing works in today’s mediatized environment. At the same time, I shall argue how these performances continue a tradition of scientific inquiry (théâtre scientifique), which traditionally tended to make a spectacle of its own experiments.

Bodies Confronted by Technologies

The opening scene of Point of View (2013), a performance by choreographer Benjamin Vandewalle, shows a dancer attached to an apparatus manipulated by another dancer. With black tape and belts his chest is connected to a rod mounted with light spots and handycams. While moving, the dancer is illuminated by the light source connected to his body; he interacts with his own shadow. As he moves, his actions are filmed from this same moving apparatus, and are projected on the rear wall. The result is a poetic dialogue between the real body on stage, its shadow, and the virtual (re)presentations of that body. When other dancers enter the scene, the whole constellation changes. The obvious relation between body, camera and projected image is disrupted. The simultaneous projection of the dancers’ movements from different points of view creates a set of visually disturbing illusions by reframing, turning, doubling and mirroring their bodies. The phenomenological perception of real and virtual bodies intermingles in a kaleidoscopic experience. An online theater critic aptly described the performance as “a choreographed and live filmed perception experiment.” (Dosogne, 2013)

It was no coincidence that this performance had its first run after a symposium entitled “The Optics of Art.1” The title refers to the central question, which was approached from different angles: how and from what position do we perceive reality, and to what extent does this position define our image of that reality? The International Film Festival in Ghent, and more particularly an exhibition on Belgian physicist Joseph Plateau (1801-1883) provided an setting for exchanges between artists and researchers interested in optical technology, perception and movement. Joseph Plateau is known for his experimental research on the principles of vision. Early in his career he organized physiques amusantes, or salon physics–small séances for a live audience, in which he demonstrated the principles of optical illusions via his “demonstration apparatus.” Plateau’s legacy as a visionary scientist was the starting point for The Optics of Art symposium, which brought contemporary media and performance artists Benjamin Vandewalle, Julien Maire and Sarah Vanagt into dialogue with scholars from theater studies, history of science and cognitive neurology, to discuss artistic and theoretical results of experiments with optics and technology. The aim was to situate Plateau’s research in optics in a broader context, by exploring the relationship between optics and performance. In what follows I will discuss how the role of these artists radically shifts from being an actor confronted with technology to being a lecturer-performer, exploring and questioning the apparatus of vision.

The Role of the Camera

Vandewalle’s Point of View is a good example of how the integration of live video on stage “opens up a multiplicity of perspectives – as Marvin Carlson puts it – a variety of ways of seeing that “never coalesce into a unified vision” (Carlson, 2008, p. 24). With this choreography for dancers, cameras and projection, Vandewalle explicitly explores questions of perception, movement and distinctive simultaneous viewpoints. The audience is challenged by the discrepancy of what one expects to see and what is actually on display: we witness how the real movements on stage – walking, kneeling, rolling on the floor – turn into projected images of that same dancing body as if it were flying, floating, falling. Inevitably one starts doubting his own perception. How can a body stand still and move at the same time?

The extensive use on stage of analogue and digital media such as film, live video, microphones and computer programs to disrupt, fragment and refract the text and bodies of “characters” has become a characterizing feature of contemporary theater and performance. Back in 1999 Hans-Thies Lehmann identified the “caesura of the media society” as one of the most crucial contexts for what has since been called the “postdramatic turn” in theater. (Lehmann, 2006, p. 22) In his famous work, Lehmann roughly distinguishes between different modes of media use. In one scenario, media are occasionally used, without this use fundamentally defining the theatrical conception. In such cases, media have a mere functional role. Or, in a second mode, its aesthetic or form serves as a source of inspiration for theater, without the media technology playing a major role in the production itself. Vandewalle’s previous performance One / Zero (2011) is a good example. With visual artist Erki De Vries he experimented with the aesthetic codes of cinema. The basic principle is that of stop-motion: different images are displayed one after another, each time interrupted by a moment of complete darkness. The cinematic movement is indefinitely delayed. “It’s like a dance, but without seeing the movement” Vandewalle points out; “each of us has to compile the movement from the individual still images.” Finally, the Wooster Group’s high-tech, intermedia aesthetics is one of Lehmann’s favorite examples of a third mode, in which media are constitutive of certain forms of theater. (Lehmann, 2006, p. 167-168) Vandewalle’s Point of View also belongs to this category.

However, here I would like to discuss another mode, not mentioned by Lehmann – the mode in which media, and more particularly the camera, becomes a central object of investigation. This is the case in the work of Benjamin Vandewalle, Julien Maire and Sarah Vanagt, who share a remarkable interest in the tension between “old” (or obsolete) and new optical media, and the way visual technology articulates inquiries into optics, cognition and visuality. The camera in the practice of these artists is not a medium for the actor’s play, but becomes the objective itself. Their theaters are laboratories for exploring what Jonathan Crary has called “regimes of seeing”; to investigate “how seeing works” (Crary, 1990, p. 3) in today’s mediatized environment. In that sense, these performances continue a scientific tradition of optical inquiry, which traditionally tended to make a spectacle of its own experiments: théâtre scientifique or physique amusante. In nineteenth-century Paris and London, the theater was a popular venue to demonstrate optical science in spectacular ways.

Dissecting Technology in the Anatomy Theater

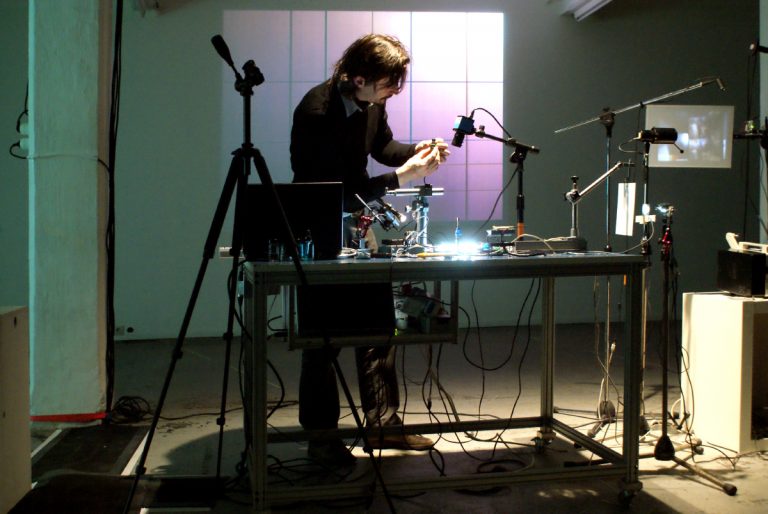

Media artist Julien Maire is inspired by earlier examples of science on theatrical display. He often performs as a surgeon or anatomist, literally dissecting and amputating cameras and other optical machines, like magic lanterns, slide projectors and webcams. His dramaturgic setting is reminiscent of the anatomy lesson, one of the early sites where modern spectatorship was constructed (see figure 2). (Bleeker, 2008) Manipulations of the slide-projector for Demi-Pas (2002), and the camera in Exploding Camera (2007) or Open Core (2009) do not simply function as a poetic deconstruction of image-making technology (see figure 3). These performative installations function, in the words of Edwin Carels, as “a laboratory to do research on our cognitive responses to an image.” (Carels, 2012, p. 189) These investigations result in original prototypes. As hybrids between media-archaeology and new (digital) technological constellations, he produces new visual experiences.

Sarah and Katrien Vanagt share this fascination with anatomical dissection and the origin of the image, especially in their contemporary rereading of historical theories of vision and the workings of the eye. Based on the Latin writings of the physician Plempius from 1632, they experimented with a camera obscura and the eye of a freshly slaughtered cow as lens. More particularly in his 1632 Ophthalmographia, Plempius emphasizes that anyone may carry out this experiment, at home, “demanding little effort and expense.” Plempius moreover describes how the cow’s eye “in the darkened room” allows the experimenter to see “behind the eye […] a painting that perfectly represents all objects from the outside world2.” In the short film In Waking Hours (2015) we see historian Katrien Vanagt as a twenty-first century disciple of Plempius3. Filmmaker Sarah Vanagt captures how this modern “Plempia” meticulously follows her teacher’s instructions. For the occasion of a symposium in Brussels, Katrien Vanagt re-enacted the experiments described by Plempius live in an anatomy theater setting, and after dissecting the animal’s eye, the audience could witness the birth of the image upon the eye4.

In a similar vein, we can understand Vandewalle’s Point of View as an optical experiment. By playing with and manipulating the classical viewing mechanism (dispositive), he emphasizes the artificiality of our perception “that is always constructed or mediated.5” His latest creation PERi-SPHERE (2015), illustrates my argument. PERi-SPHERE is a small performative installation, using a periscope. Obviously a periscope is an instrument for observing from a concealed position. It was mainly used for military purposes, to look without risk from bunkers, trenches, tanks and submarines6. Vandewalle developed an analogue version of this same idea, describing it as a performative object in which the viewer is immediately involved in the process of looking. The viewer is placed inside the apparatus, giving him a viewing position from within the technology. The apparatus in this case does not merely function as an extension of the eye, as an analogue translation of the viewer’s point of vision. Instead, the periscope provides an image of the immediate environment, but from a different point of view. What one sees is thus disconnected from the viewer’s exact physical position.

Scientific Theater

Optics has always been a central interest to both artists and scientists. Renaissance artists adopted the geometry of linear perspective and Greek optics in general. But they were equally interested in the qualities of reflected and refracted light on different materials. Historians of science have studied how pictorial artists transformed scientific knowledge of the physics of light, and how treatises on perspective offered general theories of perception. (Dupré, 2011, p. 35-60) The nineteenth century saw an increasing scientific interest in the relationship between optics, vision and perception. Optical illusions were considered an interesting means to study how the brain processed information. One result of the scientific work undertaken in this field was the creation of a number of optical toys specifically designed to trick the mind.

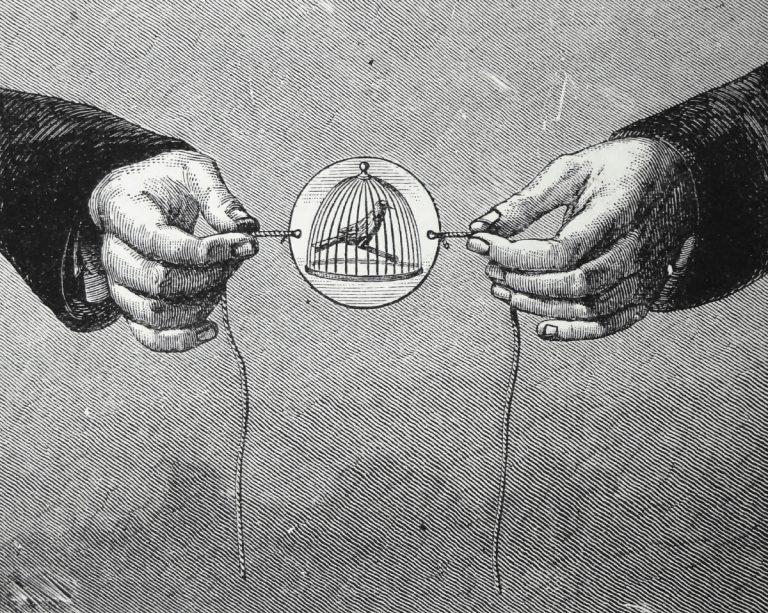

In 1827 physician John Ayrton Paris wrote a scientific book for children, which contains the first description of the principle of a scientific toy called the thaumatrope. A disk of cardboard with a picture on each side is attached to two pieces of string. When the strings are twirled quickly between the fingers the two faces of the disc appear to blend into one picture. This phenomenon was known as “the persistence of vision.” It was believed that a visual impression persists on the retina (though it is actually in the brain) for a brief interval. In 1832, scientists Joseph Plateau in Belgium and Simon Stampfer in Austria simultaneously and independently further explored this playful visual illusion, based on the Farady wheel effect, creating the “the first true moving picture toy.” Their inventions were commercialized under the name of phantasmascope (and later fantascope) in London and the Stroboskop in Vienna.

The thaumatrope, phantasmascope and the Stroboskop are beautiful examples of what have since been called “philosophical toys.” The term refers to a variety of optical toys, kinetic toys and jouets séditieux, originating in the early nineteenth century. These instruments enabled the experimental study of natural phenomena, particularly concerning vision, but they provided amusement too. They were found to have a popular as well as a scientific attraction7, challenging the boundaries of science, arts and popular culture, in between theory and practice, knowledge and amusement. (Dvořák, 2013, p. 173-196) Especially in the context of visual science, philosophical toys reflected the emergence of science as an experimental discipline. The toys’ scientific impact was dramatic, echoing their popular appeal.

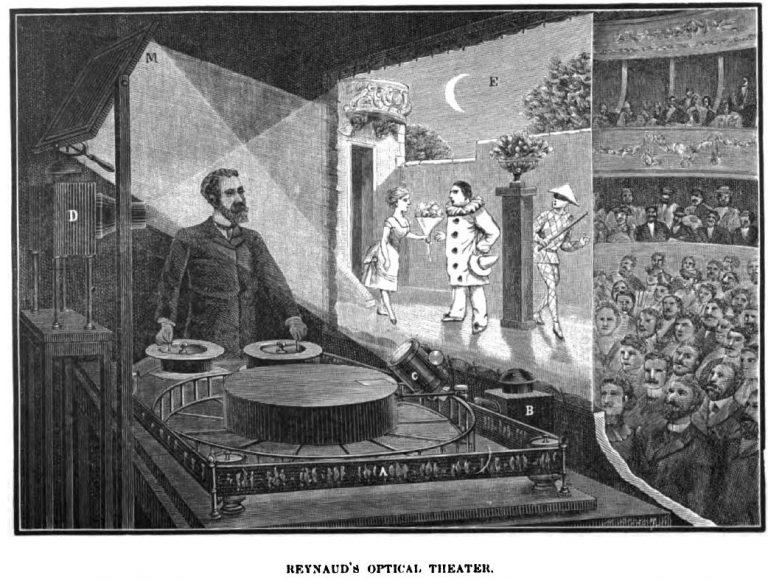

Optical media and their magical visual effects easily found their way into the theater. A beautiful example of this interchange between scientific developments and artistic and popular pursuits in the 19th century is Emile Reynaud’s Théâtre optique. After reading an article entitled “La vision et ses illusions d’optique” (1870) in the magazine La Nature, Reynaud decided to refine Plateau’s stroboscopic disc. The former assistant of Abbe Moigno (an important popularizer of science) developed the praxinoscope-théâtre. This “lilliputian theater” was based on the praxinoscope, a “device to obtain the illusion of movement with the aid of moving mirrors,” as the title of his 1877 patent reads8. A few years later he perfected the projecting praxinoscope into what has become known as the Théâtre optique. With this catoptric theater, Reynaud presented a show of “Pantomimes lumineuses” at the Musée Grevin in Paris. The well-known engraving of the event was published in the scientific journal La Nature, illustrating the optical illusion at play9.

Media Archaeology

In the past, experimental science and aesthetics shared many fundamental concerns. Making the invisible visible (or rather, making the imperceptible perceptible) by some sort of mediation is one of them. In examining the role of optical technology in contemporary performance and media art, my viewpoint will be to see them as theaters of science, as experimental platforms for measuring and qualifying the impact of these technologies on cognitive perception. Their optical instruments are objects in which scientific and aesthetic approaches intersect and overlap. This is why I propose to consider the role of the camera in these contemporary performances as comparable to the potential ascribed to modern philosophical toys. The performances’ embedded technology, as engines of the imaginary, collect, conserve and reveal foundational conceptions of vision and cognition, (Stafford, 2001) The role of a performer thus shifts from an actor embodying a character, enhanced by the use of live video, to a lecture-performer; he or she becomes a media archaeologist who excavates old or extinct media, and then becomes a surgeon who dissects and analyzes the apparatuses of vision.

In considering contemporary performance and media artists as media archaeologists and their technologies as “philosophical toys,” my approach aligns itself with parallel models of historiographical excavation. Looking to Pearson and Shanks’s seminal work on archaeology as an approach to performance studies, (Pearson and Shanks, 2001) we see that archaeology is understood less as the discovery of the past than as the establishing of an active relationship with what is left of the past. Rather then treating archaeological remains as representative tokens of a past now fragmented and to be conserved, the authors stress the return of the past in the present, but in a different guise. In the same vein, media archaeology is understood by scholars as a way to prise media history from the prevailing capitalist and teleological logic of technological progress. This emerging sub-field of media research is considered as an approach in academic research as well as in artistic practice. It does not offer a clear-cut methodology, but is necessarily a “travelling discipline” to use Mieke Bal’s phrase, cited in the introduction to Huhtamo and Parikka’s introduction to Media Archaeology. (Huhtamo and Parikka, 2011) Media archaeologists use multiple sources and diverse methods, but share a common rejection of dominant teleological accounts of media and technological history.

Old or out-dated technologies have undeniably a playful, even childlike attraction, which can even result in techno fetishism. However, by playing with optical instruments, contemporary artists not only revitalize their fascinating and magical appeal. They also illuminate the present through the past, and open up reflections on optics, media and cognition today. In her essay “The Dream Life of Technology” media artist Zoe Beloff described how through the computer she can make connections not just in theory but in practice “between the birth of technologies of the past in relation to the media revolution of the present.” She also describes the subject of her work as something that “operates in a playful spirit of philosophical inquiry.” (Beloff, 1997) In his 1987 account on “Scientific Toys,” science historian Gerard L’Estrange Turner addresses homo ludens as “a fundamental but often overlooked aspect when considering how human beings acquire knowledge.” The way in which yesterday’s science so often becomes today’s recreation does not make it any less scientific. Indeed, much scientific (and other) knowledge is absorbed consciously or unconsciously through play. (Turner, 1987, p. 384)

Philosophical toys give us a glimpse into the way our cognitive system works, creating dynamic experimental spaces within which knowledge and perception are processed and constituted. The spectators of philosophical toys are entertained. At the same time they actively participate in the process, and engage in quasi-scientific experimental instruction. Borrowing again from Beloff, the philosophical toy is an object “to think with.” In the traditional magic trick, the illusion remains mysterious because the magician keeps the secret close. But the philosophical toy has the potential to entertain and at the same time explore, expose and problematize questions about technology and perception.

In the scientific theaters of Vandewalle, Maire and Vanagt, the focus becomes the viewing subject as it experiences itself in relation to everyday media technology. The theater situation turns the nature of seeing itself into the object of conscious perception. As live experimenters with visual media, these artists playfully explore the potential and limits of perception. They are not actors confronted with technology, but lecturer-performers playfully exploring the apparatus of vision. Moreover, the work of this generation of “media-archaeologists” questions the ontological characteristics of the image, and the history of image-making technology. They experimentally explore alternative visual approaches for our contemporary, technology-saturated environment.

Notes

[1] The symposium “The Optics of Art” took place on 11 October 2013. It was on my initiative organized by the Research Centre for Visual Poetics (University of Antwerp); Cœur Volant, platform voor het Bewegende Beeld and KASK /HoGent. The exhibition “Het Plateau Effect,” curated by Edwin Carels, showed the actuality of Plateau with ten installations by David Blair, Juliana Borinski, Anna Franceschini, Adele Horne, Ann Veronica Janssens, Julien Maire, Simon Payne, Ief Spincemaille, and Benjamin Verhoeven. More information can be found on the Visual Poetics website: www.visualpoetics.be.

[2] Cited in the announcement of the documentary film In Waking Hours (2015, directed by Sarah Vanagt and Katrien Vanagt) on the website of filmmaker Sarah Vanagt: www.balthasar.be. For more information on Plempius see: Vanagt, Katrien. “Early Modern Medical Thinking on Vision and the Camera Obscura. V.F. Plempius’ Ophthalmographia,” in Horstmanshoff, Manfred, Helen King, and Claus Zittel (eds.), Blood, Sweat and Tears. The Changing Concepts of Physiology from Antiquity into Early Modern Europe, BRILL, Leiden, 2012.

[3] The installation version of In Waking Hours at the Rotterdam Film Festival in 2015 reconstructs in a domestic setting three key moments from the cultural history of the human gaze.

[4] Both film and performance were shown for the occasion of Deep Time of the Theatre, a two-day symposium I organized on contemporary theater and archaeology of media, 03-04 December 2015, a collaboration between the Université libre de Bruxelles (Fillière Arts du spectacle vivant) and the University of Antwerp’s Research Center for Visual Poetics. More information can be found on the Visual Poetics website: www.visualpoetics.be.

[5] Quote by Benjamin Vandewalle during the above-mentioned “Optics of Art” Symposium, 11 October 2013 in Ghent.

[6] Recently Apple Inc. designed an application bearing the same name. Promising the possibility to “explore the world through someone else’s eyes,” the app enables the circulation of live video.

[7] Psychologist Nicholas Wade emphasizes the fact that unlike “philosophical instruments” (instruments of the natural philosophy of the 17th and 18th centuries used for demonstrations and experimental analyses), philosophical toys are meant to be also amusing and accessible to the broader public (Wade, Nicholas J. “Philosophical Instruments and Toys: Optical Devices Extending the Art of Seeing,” Journal of the History of the Neurosciences: Basic and Clinical Perspectives, vol. 13, no. 1, 2004, p. 102-124).

[8] Only in an 1879 addition to this patent, he added the theatrical variant of the optical toy. It was based on the principle of optical compensation of prismatic mirrors (Mannoni, Laurent, David Robinson, and Donata Pesenti Campagnoni. Light And Movement. Incunabula Of The Motion Picture, 1420-1896, n.p., Torino, Museo nazionale del cinema, 1995, p. 232-33).

[9] Full title of this weekly magazine founded and edited by Gaston Tissandier in 1873, was La Nature: Revue des sciences et de leurs applications aux arts et à l’industrie. The engraving was published in the issue of 23 July 1892.

Bibliographie

– Beloff, Zoe, «The Dream Life of Technology.», en ligne, <www.zoebeloff.com>, janvier 1997.

– Bleeker, Maaike, Anatomy Live. Performance and the Operating Theater, Amsterdam, Amsterdam University Press, 2008.

– Carels, Edwin, «The Productivity of the Prototype: On Julien Maire’s Cinema of Contraptions» dans Vanderbeeken, Robrecht et al., Bastard or Playmate? Adapting Theater, Mutating Media and Contemporary Performing Arts, Amsterdam, Amsterdam University Press, 2012, p. 178-192.

– Carlson, Marvin, «Has Video Killed the Theater Star? Some German responses», Contemporary Theater Review, vol. 18, no 1, 2008, p. 20-29.

– Crary, Jonathan, Techniques of the Observer: On Vision and Modernity in the Nineteenth Century, Cambridge, MA, MIT Press, 1990.

– Dosogne, Ludo, «Point of View – Benjamin Vandewalle», en ligne, <www.cobra.be>, 14 octobre2013.

– Dupré, Sven, «The Historiography of Perspective and Reflexy-Const in Netherlandish Art», Netherlands Yearbook for History of Art / Nederlands Kunsthistorisch Jaarboek, vol. 61, 2011, p. 35-60.

– Dvořák, Tomáš, «Philosophical Toys Today», Teorie vědy / Theory of Science, vol. 35, no 2, 2013, p. 173-196.

– Huhtamo, Erki et Parikka, Jussi, Media Archaeology. Approaches, Applications, and Implications, Berkeley, University of California Press, 2011.

– Lehmann, Hans-Thies, Postdramatic Theater, Londres, Routledge, 2006.

– Mannoni, Laurent, David Robinson, et Donata Pesenti Campagnoni, Light And Movement. Incunabula Of The Motion Picture, 1420-1896, n.p., Torino, Museo nazionale del cinema, 1995.

– Pearson, Mike et Michael Shanks, Theater / Archaeology, Londres, Routledge, 2001.

– Stafford, Barbara Maria et Frances Terpak. Devices of Wonder: From the World in a Box to Images on a Screen, Los Angeles, J. Paul Getty Museum, Getty Research Institute, 2001.

– Turner, Gerard L’Estrange, «Presidential Address: ‘Scientific Toys’», British Journal for the History of Science, vol. 20, 1987, p. 377-398.

– Vanagt, Katrien, «Early Modern Medical Thinking on Vision and the Camera Obscura. V.F. Plempius’ Ophthalmographia» in Horstmanshoff, Manfred, Helen King, et Claus Zittel, Blood, Sweat and Tears. The Changing Concepts of Physiology from Antiquity into Early Modern Europe, Leyden, BRILL, 2012.

– Wade, Nicholas J., «Philosophical Instruments and Toys: Optical Devices Extending the Art of Seeing», Journal of the History of the Neurosciences: Basic and Clinical Perspectives, vol. 13, no 1, 2004, p. 102-124.